9.7 Defining Polar Coordinates and Differentiating in Polar Form

First of all, give yourself a pat on the back! You’ve made it through parametric equations (9.1, 9.2, and 9.3) and vector-valued functions (9.4 and 9.5) and tied them together in solving motion problems in 9.6. Where do we go from there?

The last section of this unit deals with polar coordinates. In our introduction, they are briefly defined as part of a two-dimensional coordinate system dealing with a line’s distance from the origin (r) and the angle said line makes with the positive x-axis (θ)… but what does that really mean?

To understand polar coordinates, we need to understand the functions that utilize them the most: polar functions!

🐻❄️ What are Polar Functions?

Polar functions, also known as circular functions, are functions commonly graphed in a polar coordinate system, which uses a distance (r) from a fixed point, known as the pole, and an angle (θ) measured counter-clockwise from the positive x-axis, to determine the coordinates of a point. These functions are often used in physics and engineering to model phenomena such as waves, orbits, and fields.

When working with polar functions, it can be difficult to differentiate them using traditional Calculus techniques because the functions are defined in terms of and , rather than and .

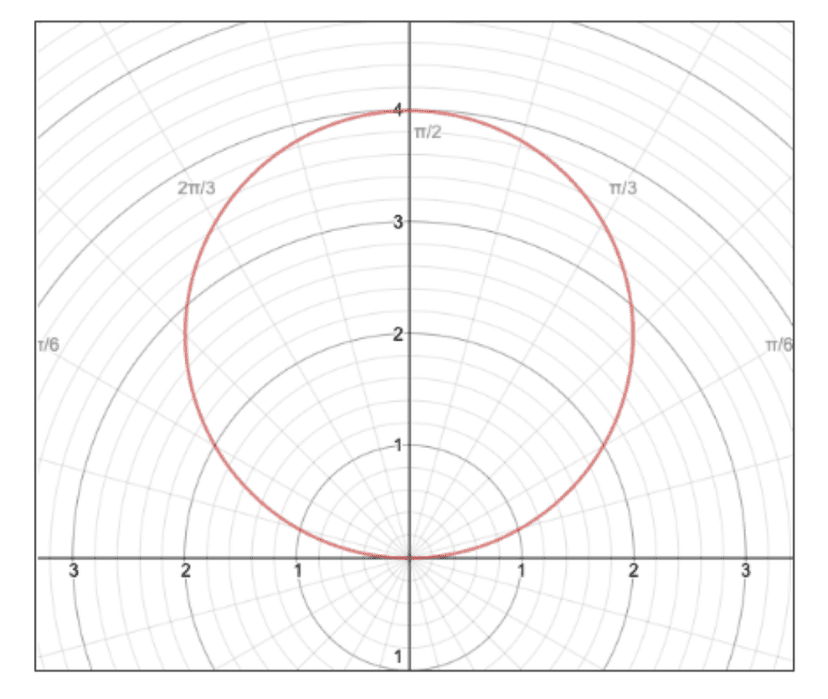

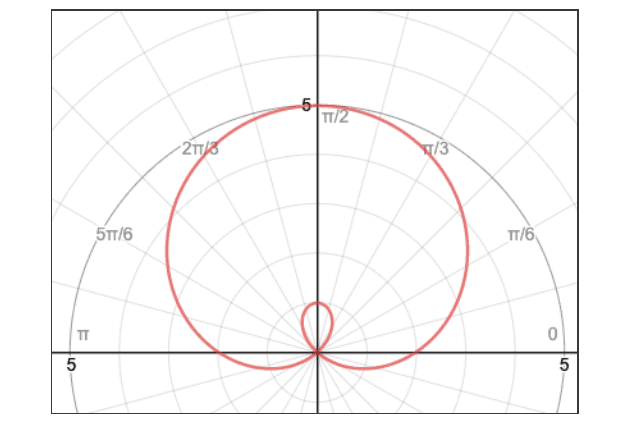

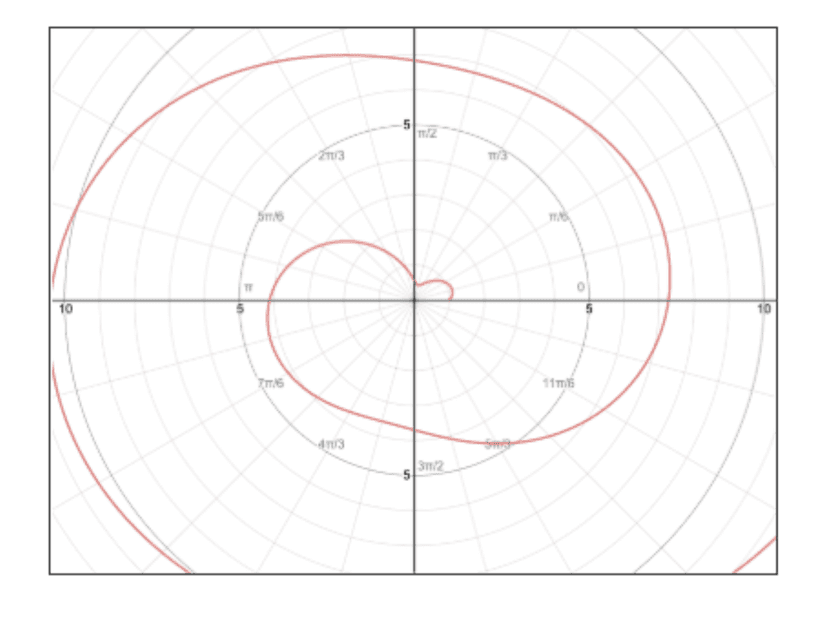

To illustrate, take a look at the graphs below:

Although they are aesthetically pleasing, it sounds like a nightmare to actually differentiate them when looking back to our definition of differentiation in the Cartesian plane—the slope of the tangent line at a point—as this doesn’t translate well in Polar-ville.

To overcome this limitation, we can convert polar equations to Cartesian equations by using the following relations:

Converting polar equations to Cartesian equations also allows us to visualize the functions more easily, as they can be graphed on a traditional x-y coordinate plane. This can be especially useful when working with complex functions that have multiple parts, such as a combination of trigonometric and polynomial functions.

Another conversion to be mindful is the following:

✏️ Converting Polar to Cartesian Practice

Let’s practice with some examples!

🥇 Converting Polar to Cartesian Example 1

Convert the following polar function to a Cartesian function:

To start, let’s rearrange our equation of interest:

Aside, let’s bring out our best friend , rearrange it, and set this equation equal to the above equation:

Now, we bring out our other best friend, the “square root” equation:

Next, we do a bit of algebra magic (aka, completing the square) and get our final Cartesian function:

Ta-da! As you might’ve noticed, converting from polar to Cartesian (or vice versa) requires familiarity with the three essential equations above, relating , , , and (with the help of sin).

Let’s change up the problem by adding values for x (or y)!

🥈 Converting Polar to Cartesian Example 2

Find the values of on where .

We have two moving pieces here: the “r = …” and the “x = 2” equations. When you have these pieces, aim to connect the two in some way or form. In this case, we can plug in our best friend into our equality:

As for the “r = …” equation, we can then plug this into what we got above:

Plugging this into your calculator (i.e., using a built-in solver function), you will get the following answers:

Slightly more challenging, huh? The general principle, though, is still the same: you use what you know about our “best friend” equations to connect , , , and . There is a pattern with these problems! 😁

💭Derivatives of Polar Functions

When we take derivatives of polar functions, we can take them as , which would give us the points that are furthest away from the origin on the polar coordinate system. We find in the same way we would find any normal derivative: by taking the derivative of the polar function.

To illustrate, let’s work with an example!

✏️ Polar Function Derivative Walkthrough

Find the points closest and furthest from the origin for , .

We derive with respect to , then set to solve for :

Thinking back to the unit circle in trigonometry, where does sin of something equal 1/2?

Normally, we’d be done but wait! The question is asking for points, not angles. This means that we want the r values. We plug these angle values back into our original equation:

Let’s do one last thing: check our endpoints, 0 and π, to see which one’s

Our final answer? The point closest to the origin (0, 0) is 0.443, and the point furthest from the origin is π (3.141…). Relative to these points, 1 and 1.128 are in between close and far. That’s it! ✅

While can tell us relative maximum and minimum values, it doesn’t tell us the slope of the tangent line, since we can’t have linear graphs on the polar coordinate system. In order to find the slope of the tangent line, we need to find the derivative on the Cartesian system, which requires us to calculate .

〰️ Slope of Tangent Line of Polar Functions

The one formula you need to know for this section:

Of course, you can memorize this formula, but most students find it much easier to simply derive it using the chain rule.

✏️ Practice Finding Tangent Line to Polar Function

Find the equation of the line tangent to the polar curve at .

Yep, that’s the same polar function we saw in the last example! This time, we’re looking for :

Substituting into the equation:

Finding the x- and y-coordinates of the tangent line given what we know about :

Therefore, the equation of the tangent line (in point-slope form) after putting everything together is:

Still confused? Let's get into further detail:

When a curve is given by a polar equation, such as , it is represented in the polar coordinate system, where the position of a point is determined by its distance r from the origin and the angle that it makes with the positive x-axis. By taking the derivatives of the function with respect to , we can learn important information about the curve, such as its curvature, concavity, and asymptotes.

🥇 The first derivative of r with respect to , denoted as , is also known as the radial component of the curve, and it represents the instantaneous rate of change of the distance from the origin. It is also used to calculate the curvature of the curve, which is a measure of how sharply the curve bends at a given point.

🥈 The second derivative of with respect to , denoted as , is also known as the radial curvature of the curve, and it represents the rate of change of the curvature. It is also used to calculate the concavity of the curve, which is a measure of whether the curve is concave up or concave down at a given point.

In addition to derivatives of , we can also find the x and y coordinates of a point on the curve in terms of by using the relations and . By taking the derivatives of and with respect to , we can learn important information about the tangent vector of the curve, and how it changes as we move along the curve.

Finally, by using the chain rule, we can find the first and second derivatives of with respect to . The first derivative is known as the slope of the curve, and it represents the rate of change of with respect to . The second derivative, again known as the curvature of the curve, represents the rate of change of the slope. 😁

🪐 Closing

…and that’s a wrap! Unlike parametric equations and vector-valued functions, polar coordinates are more finicky to work with because of the extra steps of converting between coordinate systems, applying trigonometric identities and remembering the unit circle, and oftentimes plugging into your calculator.

Even so, there is beauty in polar coordinates in a sense that we can find derivatives by applying relatively similar concepts from what we’ve learned earlier in the unit with parametric equations; only this time, we’re dealing with instead of .

Like any other Unit 9 concept, practice, practice, practice until you can hit bullseyes one after another! 🎯

💡 Key Idea: For a curve given by a polar equation , derivatives of , , and with respect to , and first and second derivatives of y with respect to can provide information about the curve.

Vocabulary

The following words are mentioned explicitly in the College Board Course and Exam Description for this topic.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| derivative | The instantaneous rate of change of a function at a specific point, representing the slope of the tangent line to the function at that point. |

| polar coordinates | A coordinate system in which points are located by their distance from a fixed point (the pole) and an angle measured from a fixed direction (the polar axis). |

| polar equation | An equation that describes a curve using polar coordinates, typically in the form r = f(θ). |

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I convert from polar coordinates to Cartesian coordinates?

To convert polar (r, θ) to Cartesian (x, y) use the standard relationships from the CED: - x = r cos θ - y = r sin θ So if a curve is given by r = f(θ), you can write x(θ) = f(θ) cos θ and y(θ) = f(θ) sin θ. That lets you treat the polar curve like a parametric curve: compute dr/dθ, then dx/dθ = dr/dθ · cos θ − f(θ)·sin θ and dy/dθ = dr/dθ · sin θ + f(θ)·cos θ. The slope dy/dx in polar form is (dy/dθ)/(dx/dθ). For second derivatives use d²y/dx² = (d/dθ(dy/dx))/(dx/dθ). These are exactly the FUN-3.G skills on the AP BC CED (use chain rule and parametric differentiation). Want a quick refresher or more examples? Check the Topic 9.7 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9/defining-polar-coordinates-differentiating-polar-form/study-guide/T4qHk9wFJdyA5ZzENJ9h) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

What's the formula for finding dy/dx when I have a polar equation?

Write x = r(θ) cos θ and y = r(θ) sin θ. Differentiate w.r.t. θ: dx/dθ = r′(θ) cos θ − r(θ) sin θ dy/dθ = r′(θ) sin θ + r(θ) cos θ Then dy/dx = (dy/dθ) / (dx/dθ), so the standard formula is dy/dx = [r′(θ) sin θ + r(θ) cos θ] / [r′(θ) cos θ − r(θ) sin θ]. Use this to get the slope of the tangent line in polar form (CED FUN-3.G.2). If dx/dθ = 0 at a θ, check for vertical tangents or polar cusps and consider limits. For second derivatives or tangent-line work, treat x and y as parametric in θ and apply the same parametric rules. For a quick review see the Topic 9.7 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9/defining-polar-coordinates-differentiating-polar-form/study-guide/T4qHk9wFJdyA5ZzENJ9h) and try practice questions at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

When do I use polar coordinates instead of regular x and y coordinates?

Use polar coordinates when the geometry or equation is naturally radial—i.e., points are best described by a distance r from the origin and an angle θ instead of x and y. Typical signs you should switch to polar: - The curve is given as r = f(θ) (spirals, roses, limaçons, circles centered on or off the origin). - The equation has trig/angle symmetry (easy symmetry about θ = 0, π/2, or periodicity in θ). - Conic sections with a focus at the origin (e.g., r = ed/(1 ± e cos θ)) or problems involving rays and angles from the origin. - Area or arc-length integrals simplify in r and θ (area element = 1/2 r^2 dθ, arc length uses x = r cosθ, y = r sinθ). Remember conversion and differentiation rules from the CED: x = r cosθ, y = r sinθ, dr/dθ, dx/dθ, dy/dθ, and dy/dx = (dy/dθ)/(dx/dθ). Use parametric-differentiation (chain rule) to find slopes, tangents, and second derivatives in polar; watch for polar cusps where dx/dθ and dy/dθ both vanish. For AP BC Topic 9.7 practice and a focused study guide, see the Fiveable study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9/defining-polar-coordinates-differentiating-polar-form/study-guide/T4qHk9wFJdyA5ZzENJ9h) and more practice problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

I'm confused about how to find the derivative of r with respect to theta - can someone explain?

If r is given as a function of θ (r = f(θ)), then dr/dθ is just the ordinary derivative f'(θ)—you find it using the usual rules (power, trig, chain rule, etc.). Where students get tripped up is using dr/dθ to get slopes in Cartesian form. Useful steps: - x = r cos θ and y = r sin θ with r = f(θ). - dx/dθ = (dr/dθ) cos θ − r sin θ. - dy/dθ = (dr/dθ) sin θ + r cos θ. - Slope dy/dx = (dy/dθ) / (dx/dθ) = [dr/dθ · sin θ + r cos θ] / [dr/dθ · cos θ − r sin θ]. So compute dr/dθ = f'(θ), plug into dx/dθ and dy/dθ, then form dy/dx. Watch for polar cusps or vertical tangents when the denominator = 0 (and numerator ≠ 0)—and for possible horizontal tangents when numerator = 0. This is exactly what the CED expects under FUN-3.G (calculating derivatives for polar curves). For extra examples, see the Topic 9.7 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9/defining-polar-coordinates-differentiating-polar-form/study-guide/T4qHk9wFJdyA5ZzENJ9h) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

What's the difference between dr/dθ and dy/dx in polar form?

dr/dθ and dy/dx are totally different derivatives—one’s how the radius changes with angle, the other’s the slope of the curve in the plane. - dr/dθ: derivative of r(θ). It tells how the distance from the origin changes as θ changes (rate of change of the polar coordinate r). This is exactly the “dr/dθ” in the CED keywords. - dy/dx (in polar): slope of the curve in Cartesian coordinates. For r = f(θ) you convert x and y: x = r cos θ, y = r sin θ, then use parametric differentiation: dx/dθ = r' cos θ − r sin θ dy/dθ = r' sin θ + r cos θ so dy/dx = (dy/dθ) / (dx/dθ) = [r' sin θ + r cos θ] / [r' cos θ − r sin θ]. This dy/dx gives the slope of the tangent line at a point (used for tangent lines, cusps, etc.—see CED FUN-3.G). If you’re studying for the AP BC exam, practice applying these formulas to find slopes and tangents (Topic 9.7 study guide: https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9/defining-polar-coordinates-differentiating-polar-form/study-guide/T4qHk9wFJdyA5ZzENJ9h). For more unit review and lots of practice problems, check the unit page (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9) and the practice bank (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

How do I find the second derivative d²y/dx² for a polar curve?

Start with x = r(θ) cosθ and y = r(θ) sinθ. Let r' = dr/dθ and r'' = d²r/dθ². Define N = r' sinθ + r cosθ and D = r' cosθ − r sinθ, so dy/dx = N/D (this is the standard polar slope). The second derivative is d²y/dx² = (d/dθ(dy/dx)) / (dx/dθ). Using the quotient rule and dx/dθ = D you get the compact formula d²y/dx² = (D·N' − N·D') / D^3, where N' = r'' sinθ + 2r' cosθ − r sinθ, D' = r'' cosθ − 2r' sinθ − r cosθ. So compute r, r', r'', form N and D, compute N' and D', and plug into (D·N' − N·D')/D^3. Watch for points where D = 0 (vertical tangents or cusps). This is exactly what the CED expects for polar differentiation (Topic 9.7). For a worked example and more practice, see the Topic 9.7 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9/defining-polar-coordinates-differentiating-polar-form/study-guide/T4qHk9wFJdyA5ZzENJ9h) and the unit practice set (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

Can someone walk me through finding dy/dx step by step for r = 2cos(θ)?

Step-by-step: 1. Write x and y in polar→Cartesian forms: - x = r cos θ = (2 cos θ)cos θ = 2 cos^2 θ - y = r sin θ = (2 cos θ)sin θ = 2 cos θ sin θ = sin(2θ) 2. Differentiate w.r.t. θ (parametric style): - dx/dθ = d(2 cos^2 θ)/dθ = 2·2 cos θ·(−sin θ) = −4 cos θ sin θ = −2 sin(2θ) - dy/dθ = d[sin(2θ)]/dθ = 2 cos(2θ) 3. Use dy/dx = (dy/dθ) / (dx/dθ): - dy/dx = [2 cos(2θ)] / [−2 sin(2θ)] = − cos(2θ)/sin(2θ) = −cot(2θ) Notes: - So dy/dx = −cot(2θ). This is undefined where sin(2θ)=0 (θ = n·π/2), which gives vertical tangents or cusps—check r and the curve there. - This uses the AP CED ideas: x = r cos θ, y = r sin θ, differentiate wrt θ and form dy/dx (FUN-3.G). If you want worked examples or practice problems, see the Topic 9.7 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9/defining-polar-coordinates-differentiating-polar-form/study-guide/T4qHk9wFJdyA5ZzENJ9h) or the Unit 9 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9).

I don't understand why we need to use the chain rule when differentiating polar equations.

You need the chain rule because in polar form x and y are not direct functions of x—they’re both functions of θ: x = r(θ)cosθ and y = r(θ)sinθ. Each is a product of r(θ) (a function of θ) and a trig function of θ, so when you differentiate x or y with respect to θ you use the product rule and the chain rule for r(θ). Then to get dy/dx you treat the curve parametrically and use dy/dx = (dy/dθ)/(dx/dθ). Concretely, dx/dθ = r′(θ)cosθ − r(θ)sinθ dy/dθ = r′(θ)sinθ + r(θ)cosθ so dy/dx = (dy/dθ)/(dx/dθ). That chain-of-dependence (r depends on θ) is exactly why the chain rule shows up. This is what the CED calls “parametric differentiation” in polar coordinates and it’s how you find slopes, tangent lines, cusps, and second derivatives in Topic 9.7 (see the study guide) (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9/defining-polar-coordinates-differentiating-polar-form/study-guide/T4qHk9wFJdyA5ZzENJ9h). For more practice, check unit review and tons of problems (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9 and https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

What's the relationship between x = rcos(θ) and y = rsin(θ) when finding derivatives?

Think of x = r(θ) cos θ and y = r(θ) sin θ as parametric equations with parameter θ. When you differentiate with respect to θ you get dx/dθ = r′(θ) cos θ − r(θ) sin θ dy/dθ = r′(θ) sin θ + r(θ) cos θ. The slope dy/dx of the polar curve is the quotient (chain rule / parametric rule): dy/dx = (dy/dθ) / (dx/dθ) = [r′ sin θ + r cos θ] / [r′ cos θ − r sin θ]. Use that on the AP to find tangent slopes, vertical/horizontal tangents (set numerator or denominator = 0), and to detect polar cusps (both numerator and denominator 0). If you need the second derivative for concavity, differentiate dy/dx with respect to θ and divide by dx/dθ (d²y/dx² = (d/dθ(dy/dx))/(dx/dθ)). This matches the CED keywords (r(θ), dr/dθ, dx/dθ, dy/dθ, dy/dx) in Topic 9.7. For a clear worked example and practice, see the Topic 9.7 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9/defining-polar-coordinates-differentiating-polar-form/study-guide/T4qHk9wFJdyA5ZzENJ9h) and try related practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

How do I know when a polar curve has a horizontal or vertical tangent line?

Use x = r(θ) cosθ and y = r(θ) sinθ and treat θ like the parameter. Then dy/dx = (dy/dθ)/(dx/dθ) = (r′(θ) sinθ + r(θ) cosθ) / (r′(θ) cosθ − r(θ) sinθ). - Horizontal tangent: numerator = 0 and denominator ≠ 0. Solve r′(θ) sinθ + r(θ) cosθ = 0; check the denominator isn’t zero at that θ. - Vertical tangent: denominator = 0 and numerator ≠ 0. Solve r′(θ) cosθ − r(θ) sinθ = 0; check the numerator isn’t zero there. If both numerator and denominator are 0, the slope is indeterminate—often a cusp or need to examine limits (or convert to parametric form and use L’Hospital or higher derivatives). Also watch points where r(θ)=0 (the curve passes through the pole), which can create cusps; analyze limits of dy/dx near that θ. This is exactly what the CED expects for FUN-3.G derivatives in polar form. For a quick review and examples, see the Topic 9.7 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9/defining-polar-coordinates-differentiating-polar-form/study-guide/T4qHk9wFJdyA5ZzENJ9h). For extra practice, check Fiveable’s AP Calc practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

Why do I keep getting confused between differentiating with respect to θ versus differentiating with respect to x?

You're mixing up the independent variable. In polar form r = f(θ) the curve is parameterized by θ, not x. So whenever you differentiate, ask: “Which quantity is changing with the input?” Use the chain/parametric idea from the CED keywords: - x = r(θ) cos θ and y = r(θ) sin θ, so compute dx/dθ and dy/dθ (differentiate both r and the trig factors). - The slope dy/dx is then dy/dθ divided by dx/dθ: dy/dx = (dy/dθ) / (dx/dθ). That’s just parametric differentiation applied to polar (FUN-3.G.2). - For second derivative use d²y/dx² = (d/dθ(dy/dx)) / (dx/dθ). Practical tip: when a problem asks for slope of tangent, find dy/dx at the specific θ (you don’t differentiate w.r.t. x directly). If dx/dθ = 0 at that θ, check for vertical tangent or cusp (polar cusps). For more worked examples and AP-aligned practice see the Topic 9.7 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9/defining-polar-coordinates-differentiating-polar-form/study-guide/T4qHk9wFJdyA5ZzENJ9h) and thousands of practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

What's the formula for finding dx/dθ and dy/dθ in polar coordinates?

If a polar curve is r = f(θ) with x = r cos θ and y = r sin θ, differentiate with respect to θ (use the product and chain rules): - dx/dθ = dr/dθ · cos θ − r · sin θ - dy/dθ = dr/dθ · sin θ + r · cos θ Then the slope dy/dx of the tangent line is dy/dx = (dy/dθ) / (dx/dθ) (provided dx/dθ ≠ 0). These come straight from FUN-3.G in the CED: you use dr/dθ and the parametric form x(θ), y(θ) to get first and second derivatives and info about tangents and cusps. For more practice and the Topic 9.7 study guide, see the Fiveable resource (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9/defining-polar-coordinates-differentiating-polar-form/study-guide/T4qHk9wFJdyA5ZzENJ9h). For broader Unit 9 review and lots of practice problems, check (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9) and (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

How do I find where a polar curve has critical points or turning points?

Think of a polar curve r = f(θ) like a parametric curve x = r(θ) cosθ, y = r(θ) sinθ. To find turning (critical) points on the graph: - Compute dx/dθ = r′(θ) cosθ − r(θ) sinθ and dy/dθ = r′(θ) sinθ + r(θ) cosθ (use chain rule). - The slope is dy/dx = (dy/dθ)/(dx/dθ). Horizontal tangents: dy/dx = 0 → numerator = 0 (dy/dθ = 0) while dx/dθ ≠ 0. Vertical tangents: dy/dx undefined → denominator = 0 (dx/dθ = 0) while dy/dθ ≠ 0. - Classify each solution by checking sign changes of dy/dx (or compute d²y/dx² in polar form) just like in parametric work. - Watch r = 0: if r = 0 and r′ ≠ 0 you may get a cusp (special case to test). This is exactly FUN-3.G territory in the CED (compute r′, x′, y′ and dy/dx). For step-by-step examples and practice, see the Topic 9.7 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9/defining-polar-coordinates-differentiating-polar-form/study-guide/T4qHk9wFJdyA5ZzENJ9h) and try more problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

I missed class - can someone explain what polar coordinates even are and why we use them?

Think of polar coordinates as another way to locate points: instead of (x,y) you use (r, θ) where r is distance from the origin and θ is the angle from the positive x-axis. They’re handy when a curve is naturally described by angle—circles, spirals, roses—because equations like r = f(θ) can be much simpler than in Cartesian form. Key formulas you’ll use (from the CED keywords): x = r cos θ, y = r sin θ, dr/dθ. To get slopes and tangents you treat θ like a parameter: dx/dθ = dr/dθ·cos θ − r·sin θ, dy/dθ = dr/dθ·sin θ + r·cos θ, and dy/dx = (dy/dθ)/(dx/dθ). Second derivatives and tangent-line info follow from parametric rules (watch for polar cusps where dx/dθ = dy/dθ = 0). On the AP BC exam, you’ll be expected to compute these derivatives and use them to find slopes, tangents, and concavity. For a focused review, check the Topic 9.7 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9/defining-polar-coordinates-differentiating-polar-form/study-guide/T4qHk9wFJdyA5ZzENJ9h) and hit the AP practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus) for extra practice.

When solving FRQ problems about polar curves, what information can I get from the first and second derivatives?

Use the polar-to-parametric link: x = r(θ) cosθ, y = r(θ) sinθ, with dx/dθ = r′(θ) cosθ − r(θ) sinθ and dy/dθ = r′(θ) sinθ + r(θ) cosθ. Then dy/dx = (dy/dθ)/(dx/dθ) and d²y/dx² = (d/dθ(dy/dx))/(dx/dθ). What the first derivative gives you (dy/dx): - Slope of the tangent line; plug into point-slope to write the tangent (common FRQ task). - Horizontal tangents when dy/dθ = 0 (and dx/dθ ≠ 0); vertical tangents when dx/dθ = 0 (and dy/dθ ≠ 0). - Places where dx/dθ = dy/dθ = 0 often indicate cusps or places to check more carefully (e.g., loops or pole crossings). What the second derivative gives you (d²y/dx²): - Concavity of the curve in xy-plane and locations of inflection points (sign changes of d²y/dx²). - Helps confirm whether a stationary tangent is a local max/min of y vs x (use sign of d²y/dx²). For exam alignment see FUN-3.G in the CED; review the Topic 9.7 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-9/defining-polar-coordinates-differentiating-polar-form/study-guide/T4qHk9wFJdyA5ZzENJ9h) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).