1.8 Determining Limits Using the Squeeze Theorem

Welcome back to AP Calculus with Fiveable! This topic focuses on determining the limit of a function based on information given about other functions that bound it. We’ve worked through determining limits through algebraic manipulation, graphs, and tables, so let's keep building our limit skills. 🙌

⌛ Squeeze Theorem

Before we get into the nitty gritty, be sure to review some of the content we’ve already went over!

📚 Background Knowledge

To effectively use the Squeeze Theorem, you should be familiar with:

- Limits: Understanding how functions behave near a specific value.

- Basic Function Behavior: Knowledge about how functions like sine, cosine, exponential, etc., behave for different inputs.

🧩 What is the Squeeze Theorem?

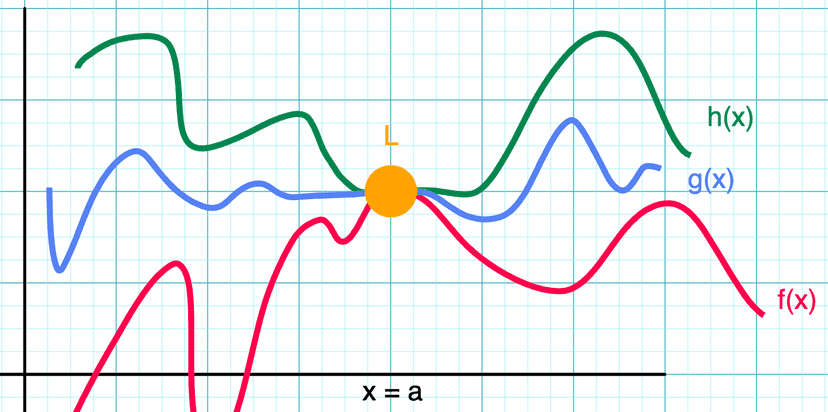

The squeeze theorem states that if and , then must also . Take a look at the visual below!

We can see that the function is sandwiched between and , so it must follow the same rule in the shown interval.

🧮 Squeeze Theorem Practice Problems

Let’s work on a few questions and make sure we have the concept down!

1) Squeeze Theorem Logic

Functions and are twice-differentiable functions with It is known that for . Let k be a function satisfying for

. Is continuous at ? Justify your answer.

Once you’re ready, keep on reading to see how to approach this question. ⬇️

If functions and are twice-differentiable, they must be continuous. Therefore, and . Since and the conditions for continuity are met, the squeeze theorem for applies at . So, .

Since , must equal .

We can then conclude that is continuous at because . Brush up on continuity rules with this guide here: Confirming Continuity Over an Interval.

This question is from the 2019 AP Calculus AB examination administered by College Board. All credit to College Board. Way to go! 👏

2) Computing a Limit Using Squeeze Theorem

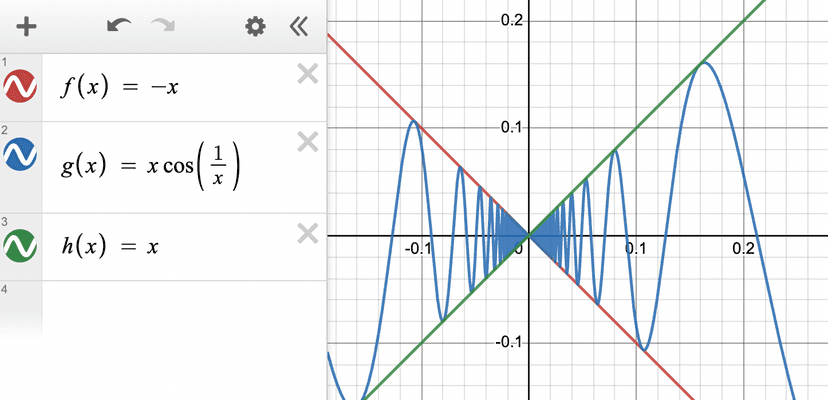

Find the limit of the function as approaches 0, using the Squeeze Theorem.

In this case, we can use the fact that for all to create a bounding function.

Multiply the inequality by , and then consider the bounding functions and so that .

Since , and the functions are known to be continuous, the Squeeze Theorem can be applied. Let’s check the limits of the bounding functions as they approach 0 to see if they squeeze at .

Because , the Squeeze Theorem holds true, and…

Check out the graph below to confirm our answer visually!

You nailed it! This was a tough one. 💪

🌟 Closing

Great work! 🙌 The squeeze theorem is a key foundational idea for AP Calculus. You can anticipate encountering questions involving limits and the squeeze theorem on the exam, both in multiple-choice and as part of a free response.

If you’d like some steps to follow, here they are:

- 🤔 Identifying the Function: Recognize the function for which you need to determine the limit.

- 👀 Finding the 'Squeeze' Functions: Locate two functions that 'squeeze' the given function between them.

- 🏁 Ensuring Known Limits: Confirm that the limits of the 'squeezing' functions are known as x approaches the same value.

You got this! 🤩

Vocabulary

The following words are mentioned explicitly in the College Board Course and Exam Description for this topic.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| equivalent expressions | Different algebraic forms of the same function that have the same value. |

| limit | The value that a function approaches as the input approaches some value, which may or may not equal the function's value at that point. |

| squeeze theorem | A method for determining the limit of a function by showing that the function is bounded between two other functions that have the same limit at a point. |

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I use the squeeze theorem to find limits?

The squeeze theorem says: if f(x) ≤ g(x) ≤ h(x) near a (except maybe at a) and lim_{x→a} f(x) = lim_{x→a} h(x) = L, then lim_{x→a} g(x) = L. To use it on a limit: 1. Find two simpler functions f and h that bound g from below and above for x near the limit point. 2. Prove the inequalities hold (often trig inequalities or algebraic manipulation). 3. Evaluate the limits of the bounds. If both equal the same L, conclude the middle function’s limit is L. Classic AP examples: use geometric/trig inequalities to show cos x ≤ 1 and −1 ≤ sin x ≤ 1 to get lim_{x→0} sin x / x = 1 and lim_{x→0} (1−cos x)/x = 0 (see CED EK LIM-1.E.2). Squeeze-theorem problems often appear on AP sections testing LIM-1.E; be ready to justify the bounds briefly. For guided practice and examples, check the Topic 1.8 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/determining-limits-using-squeeze-theorem/study-guide/0Ax6y3Qku88ex24KGwiG) or try practice problems at Fiveable (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

What's the squeeze theorem and when do I use it instead of direct substitution?

The squeeze theorem says: if g(x) ≤ f(x) ≤ h(x) near a (except maybe at a) and lim_{x→a} g(x) = lim_{x→a} h(x) = L, then lim_{x→a} f(x) = L. You use it when direct substitution fails (like 0/0 or undefined) and you can bound the troublesome function between two simpler functions whose limits you know. Classic AP examples from the CED: lim_{x→0} sin x / x = 1 and lim_{x→0} (1 − cos x)/x = 0—both are shown by bounding with trig inequalities or geometric arguments. Use direct substitution whenever the function is continuous at the point (substitution gives the limit). Use the squeeze theorem when you can’t simplify algebraically but can find upper and lower bounds that squeeze to the same value. For an AP-focused study guide and worked examples, see the Topic 1.8 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/determining-limits-using-squeeze-theorem/study-guide/0Ax6y3Qku88ex24KGwiG). For extra practice, try problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

Can someone explain the squeeze theorem step by step with an example?

Squeeze theorem idea (step-by-step)—example: lim(x→0) (1 − cos x)/x = 0. 1) Find two functions that “trap” your function near the limit point. Use trig identity: 1 − cos x = 2 sin^2(x/2). So 0 ≤ 1 − cos x = 2 sin^2(x/2). 2) Bound sin^2 by a simpler function. For small u, |sin u| ≤ |u|, so 0 ≤ 2 sin^2(x/2) ≤ 2 (x/2)^2 = x^2/2. 3) Divide the inequality by x (for x ≠ 0), keeping sign info: for x→0 we can write 0 ≤ (1 − cos x)/x ≤ x/2 for x near 0 (taking x>0; similar for x<0 gives same limit). 4) Take limits of the two bounds as x→0: lim x→0 0 = 0 and lim x→0 x/2 = 0. 5) By the squeeze (sandwich) theorem, the middle expression has the same limit: lim x→0 (1 − cos x)/x = 0. This is exactly the kind of CED example (LIM-1.E.2). For another classic, use the unit-circle geometric bounds to squeeze sin x/x → 1 as x→0. For more worked examples and AP-style practice, see the Topic 1.8 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/determining-limits-using-squeeze-theorem/study-guide/0Ax6y3Qku88ex24KGwiG) and try problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

I'm confused about how to find the two functions that squeeze my function - how do I pick them?

Think of the squeeze theorem like picking two simple “fences” that you already know squeeze your complicated function. Tips to pick them: - Look for obvious inequalities. If your function has sin, cos, or absolute values, use standard bounds: −1 ≤ sin x ≤ 1, |f(x)| ≤ g(x), or for 0

What's the formula for the squeeze theorem and how do I apply it?

Squeeze theorem (sandwich theorem) formula: if f(x) ≤ g(x) ≤ h(x) for all x near a (except maybe at a) and lim_{x→a} f(x) = lim_{x→a} h(x) = L, then lim_{x→a} g(x) = L. How to apply (step-by-step): 1. Find two simpler functions f and h that bound your function g: f(x) ≤ g(x) ≤ h(x) for x near the limit point. 2. Compute the limits of f and h as x→a. 3. If those two limits are equal (call it L), conclude lim_{x→a} g(x) = L. Two classic AP examples (appear in the CED for Topic 1.8): - Show lim_{x→0} (sin x)/x = 1 by using geometric trig inequalities from the unit circle to get cos x ≤ (sin x)/x ≤ 1 for small |x|, then both bounds → 1. - Show lim_{x→0} (1 − cos x)/x = 0 by noting 0 ≤ (1 − cos x)/x ≤ x/2 (or another suitable bound) and both bounds → 0. On the AP exam you may be asked to justify bounds or use trig inequalities; be ready to state the bounding inequalities and compute the two outer limits. For a quick topic review, check the Fiveable study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/determining-limits-using-squeeze-theorem/study-guide/0Ax6y3Qku88ex24KGwiG). For more practice, use https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus.

When do I know I need to use the squeeze theorem vs other limit methods?

Use the squeeze theorem when you can find two simpler functions that “trap” your function and both have the same limit at the point. Practically, that often happens when: - The function oscillates but is bounded (like f(x)=sin x) and is multiplied by something that → 0 (e.g., x·sin(1/x) or sin x / x). - You recognize a standard trig limit (sin x / x → 1 or (1 − cos x)/x → 0) but can’t simplify algebraically, so you bound using trig inequalities or a unit-circle argument. - The expression is hard to algebraically simplify but you can produce obvious upper/lower bounds that converge to the same value. Before using squeeze, try algebraic factoring, limit laws, substitution, or L’Hôpital’s Rule (when applicable and conditions hold). If those fail or the function is naturally trapped between two simpler limits, squeeze is the right tool. On the AP exam you should state the inequalities, show both bounding limits equal the same value, and cite the squeeze theorem (see examples in the CED: sin x/x and (1−cos x)/x). For a quick review and examples, see the Topic 1.8 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/determining-limits-using-squeeze-theorem/study-guide/0Ax6y3Qku88ex24KGwiG). For extra practice, try problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

How do I solve lim x approaches 0 of sin x over x using squeeze theorem?

Use the unit-circle inequalities and the Squeeze Theorem. For 0 < x < π/2 the geometric facts give sin x < x < tan x = sin x / cos x. Divide the chain by x (positive) and rearrange to get cos x < sin x / x < 1. As x → 0+, cos x → 1 and the right-hand bound is 1, so by the Squeeze Theorem sin x / x → 1. For x → 0− use oddness: sin(−x)/(−x) = sin x / x, so the same limit holds from the left. Therefore lim_{x→0} (sin x)/x = 1. This is the classic CED illustrative example for Topic 1.8 (LIM-1.E.2). If you want a step-by-step geometric proof or an ε–δ justification, check the Topic 1.8 study guide on Fiveable (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/determining-limits-using-squeeze-theorem/study-guide/0Ax6y3Qku88ex24KGwiG) and practice more problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

I don't understand how the squeeze theorem works - why does it even work?

Think of the squeeze theorem like a sandwich: if f(x) is always between two functions g(x) ≤ f(x) ≤ h(x), and both g and h get arbitrarily close to the same number L as x → a, then f has no room but to be close to L too. Intuitively, once g and h are within, say, ±ε of L for x near a, f—being stuck between them—must also lie within ±ε of L. A compact epsilon–delta sketch: for any ε>0 pick δ so both |g(x)−L|<ε and |h(x)−L|<ε when 0<|x−a|<δ. Then g(x)≥f(x)≥h(x) implies |f(x)−L|<ε, proving the limit is L. That’s exactly how we justify limits like lim_{x→0} (sin x)/x = 1 using trig bounds from the unit circle. For step-by-step examples and practice aligned to the AP CED (LIM-1.E), see the Topic 1.8 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/determining-limits-using-squeeze-theorem/study-guide/0Ax6y3Qku88ex24KGwiG). For more problems, check Fiveable’s practice set (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

What's the difference between using L'Hopital's rule and the squeeze theorem for limits?

Good question—they’re different tools for different situations. - L’Hôpital’s Rule: use when a limit gives an indeterminate form 0/0 or ∞/∞ and both numerator and denominator are differentiable near the point. You can replace the original limit with the limit of their derivatives (provided that new limit exists). Good for algebraic or analytic expressions like (e^x−1)/x as x→0. - Squeeze (Sandwich) Theorem: use when you can bound your function between two simpler functions that have the same limit at the point. This is essential for trig limits and geometric arguments—e.g., sin x / x → 1 as x→0 is usually shown by trig inequalities and the unit-circle argument (CED LIM-1.E.2). Squeeze works even if derivatives don’t exist or L’Hôpital’s hypotheses fail. AP tip: know both. On the exam, use squeeze for trig/inequality arguments (Topic 1.8), and use L’Hôpital only when you can justify differentiability and an indeterminate form. For the Topic 1.8 study guide see (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/determining-limits-using-squeeze-theorem/study-guide/0Ax6y3Qku88ex24KGwiG). For more practice, try the problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

How do I find the upper and lower bounds when using squeeze theorem?

Think: you need two simpler functions that squeeze your function from below and above and both have the same limit at the point. How to get those bounds: 1. Look for known inequalities or simple comparisons. Common tools: -1 ≤ sin x ≤ 1, |sin x| ≤ |x| (near 0), 1−cos x ≥ 0 and 1−cos x ≤ x^2/2 (from Taylor/geometry), monotonicity, or algebraic manipulation (factor, multiply by conjugate). 2. Rewrite the function so you can apply a known bound. Example: for 0 < x < π/2, cos x ≤ (sin x)/x ≤ 1. So cos x ≤ sin x/x ≤ 1 and both cos x and 1 → 1 as x → 0, so sin x/x → 1 (this is the squeeze used in the CED example). 3. Use absolute-value bounds when sign isn’t fixed. If |f(x)| ≤ g(x) and g(x) → 0, then f(x) → 0. 4. Check endpoints and one-sided limits: make sure the inequalities hold on the interval you’re approaching from. If you want more worked examples and practice (including the two CED examples sin x/x and (1−cos x)/x), see the Topic 1.8 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/determining-limits-using-squeeze-theorem/study-guide/0Ax6y3Qku88ex24KGwiG) and try problems at Fiveable practice (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

Can you show me how to prove that the limit of sin x over x equals 1 using squeeze theorem?

Take 0 < x < π/2 (same idea works for small negative x by symmetry). On the unit circle one gets the standard inequalities sin x < x < tan x = sin x / cos x. Divide through by x·(>0) to get (sin x)/x < 1 < (sin x)/(x·cos x). Equivalently, dividing the middle chain by (x/ sin x) or taking reciprocals carefully gives cos x < (sin x)/x < 1. As x → 0+, cos x → 1, so by the squeeze theorem (cos x ≤ (sin x)/x ≤ 1) we conclude lim_{x→0} (sin x)/x = 1. For x < 0 note (sin x)/x is even ((sin(−x))/(−x) = (sin x)/x), so the same limit holds from the left; hence the two-sided limit is 1. This is the classic squeeze-theorem proof used on the AP CED (Topic 1.8). For a quick review, see the Topic 1.8 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/determining-limits-using-squeeze-theorem/study-guide/0Ax6y3Qku88ex24KGwiG). For extra practice, try related problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

I keep getting confused about which function goes on top and bottom in the squeeze - help?

Think of the squeeze as “which one’s bigger?”—put the larger function on top and the smaller on the bottom. The goal is to find two simpler functions g(x) ≤ f(x) ≤ h(x) near the limit point, where both g and h have the same limit L; then f must also tend to L by the squeeze theorem (CED EK LIM-1.E.2). Quick checklist:

- Identify simple bounds you already know (e.g., −1 ≤ sin x ≤ 1, cos x ≤ 1, or the geometric inequality sin x ≤ x ≤ tan x for 0

When I have a limit that equals 0/0, should I use squeeze theorem or L'Hopital's rule?

If a limit gives 0/0, that just tells you it’s indeterminate—it doesn’t force one method. Pick the tool that fits the function. Quick checklist: - Can you algebraically simplify (factor, cancel, rationalize)? Do that first—it’s often enough. - Is the expression a trig limit like sin x/x or (1 − cos x)/x near 0? Those are classic squeeze-theorem cases (use inequalities or the unit-circle argument). See Topic 1.8 in the Fiveable study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/determining-limits-using-squeeze-theorem/study-guide/0Ax6y3Qku88ex24KGwiG). - Are numerator and denominator differentiable near the point and the derivative limit easier to find? Then L’Hôpital’s Rule is convenient: if lim f = lim g = 0 (or ±∞) and lim f′/g′ exists, then lim f/g = lim f′/g′. - If neither applies, try series expansion or bounding (squeeze). Remember AP expectations: use the squeeze theorem where bounding/inequalities are natural (trig examples in the CED), and use L’Hôpital when differentiation simplifies the limit. For more practice problems and examples, check the Unit 1 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1) and the AP practice bank (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

How do I know if my squeeze theorem setup is correct before I solve the limit?

You can check your squeeze setup quickly with three things: 1. Inequality valid on a punctured neighborhood: show g(x) ≤ f(x) ≤ h(x) for all x near a (except maybe at a). Don’t just test one x—either derive the inequality algebraically or argue from known facts (e.g., |sin x| ≤ 1, or 1 − cos x ≥ 0). 2. Both bounds have the same limit at a: compute lim_{x→a} g(x) and lim_{x→a} h(x). If they’re equal to L, you’ve met the second required hypothesis of the squeeze theorem (CED EK LIM-1.E.2). 3. Check endpoints / one-sided behavior: if you need a one-sided limit, make sure the inequalities hold from that side only. Also verify you didn’t accidentally reverse an inequality when multiplying/dividing by something that can change sign. Quick sanity checks: plug in values close to a to see the inequality numerically, and compare to standard squeezes (e.g., −1 ≤ sin x ≤ 1 gives −1/|x| ≤ sin x/x ≤ 1/|x| for x≠0) or the sin x / x and (1−cos x)/x examples in the AP study guide (see the Topic 1.8 study guide: https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/determining-limits-using-squeeze-theorem/study-guide/0Ax6y3Qku88ex24KGwiG). For more practice problems, use the AP practice bank (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

What are some common functions that require the squeeze theorem to find their limits?

Good question—the squeeze theorem shows up when a function oscillates or is hard to simplify but you can tightly bound it. Common examples you should memorize and recognize on the AP exam: - sin x / x as x → 0 (limit = 1) and (1 − cos x)/x as x → 0 (limit = 0)—classic trig uses of trigonometric inequalities and the unit-circle geometric argument (CED: sin(x)/x limit, (1−cos x)/x limit). - x·sin(1/x) or x^2·sin(1/x) as x → 0: use −|x| ≤ x·sin(1/x) ≤ |x| to get limit 0. - Functions of the form f(x)·g(x) where g(x) oscillates between −1 and 1 (e.g., sin(1/x)) and f(x) → 0. - Sequence analogues a_n = b_n·sin(c_n) where b_n → 0—squeeze for sequences. On the AP exam you’ll need to justify bounds (inequalities) and connect them to the limit (LIM-1.E). For a focused review, see the Topic 1.8 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/determining-limits-using-squeeze-theorem/study-guide/0Ax6y3Qku88ex24KGwiG). For extra practice, try problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).