In this study guide, we’ll review how limits can be defined and how to use limit notation. Understanding limits is like peeking into the future of a function as it approaches a specific value. By the end of this reading, you’ll have a strong grasp of this critical AP Calculus skill. Let's get started by breaking down the key aspects of defining limits and using different notation forms.

🤔 Defining a Limit

At its core, a limit is the y-value of a function, , when it approaches the value . Commonly, it is notated as , which is read as “the limit of as approaches ”.

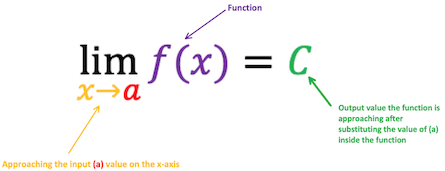

The visual below breaks down the different parts of the equation, which is how we represent limits analytically:

The notation indicates that as x approaches a, the function f(x) approaches the correct number C.

Image Courtesy of Study.com

This notation tells us that as x gets closer and closer to the value , the function f(x) inches closer and closer to the real number . Remember that the limit is not equal to , but rather gets closer and closer to it.

🤨 Representing Limits Numerically & Graphically

Limits can also be expressed numerically and graphically. Numerically, you might create a table of values approaching from both sides. Graphically, you can observe how the function approaches a certain height as gets closer to .

🔢 Representing Limits Numerically

Consider the following function:

We're interested in finding the limit of this function as approaches .

Let's set up a table of values where approaches from both the left and the right side:

| Approaching from the left () | Approaching from the left () |

|---|---|

| 0.9 | 1.1 |

| 0.99 | 1.01 |

| 0.999 | 1.001 |

| 0.9999 | 1.0001 |

Notice how we’re getting as closer as possible to the value 1 from both the right and left sides. Now, let’s calculate the corresponding values of by plugging each of these values in.

⬅️ Viewing the Limit from the Left Side

For :

When plugging in …

When plugging in …

When plugging in …

When plugging in …

We can already see that as gets closer and closer to , approaches and gets closer to .

➡️ Viewing the Limit from the Right Side

For :

When plugging in …

When plugging in …

When plugging in …

When plugging in …

We can also see that as gets closer to 1 from the right side, gets closer to 2! This suggests that:

This numerical representation really shows you how the function approaches a particular value as x gets arbitrarily close to the specified value.

We’ll get into estimating limit values from tables in key topic 1.4! This just gives you an idea of how limits can be represented numerically. 😄

📉 Representing Limits Graphically

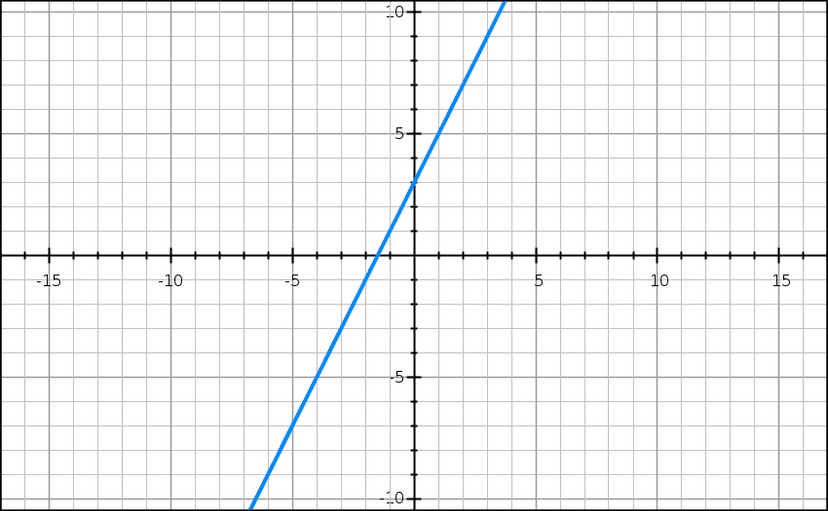

Consider the linear function . We want to investigate the limit of this function as approaches 1, or . As approaches 1, let's visualize how the function behaves graphically.

Graph displaying the function f(x) = 2x+3

Image Courtesy of GraphSketch.com

As approaches 1 from the left and from the right , the function values smoothly progress along the straight line, converging towards a specific y-value. This limit statement indicates that as gets arbitrarily close to 1, the function approaches the value 5.

We’ll get into estimating limits from graphs more in the next key topic!

💡 Remember, limits are not just numbers; they signify behavior and tendencies. They describe how a function behaves near a point, rather than at a specific point.

✏️Defining Limits: Practice Problems

When you go through these two practice problems, think of going through two different steps:

- ⚡ Substitute the value into the limit.

- 🧮 Evaluate the limit.

Go ahead and give it a try!

-

Consider the function . What is the value of ?

A. 3

B. 5

C. 6

D. 7

-

Consider the function . What is the value of ?

A. -8

B. 8

C. 9

D. 1

☑️ Defining Limits: Solutions to Practice Problems

-

To solve this question, follow these steps:

- Substitute the value: =

- Evaluate the limit: Substitute

Therefore, the correct answer is: B) 5

-

To solve this question, follow these steps:

- Substitute the value: =

- Evaluate the limit: Substitute

Therefore, the correct answer is: A) -8

Vocabulary

The following words are mentioned explicitly in the College Board Course and Exam Description for this topic.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| analytic notation | The symbolic mathematical representation of a limit, typically written as lim(x→a) f(x) = L. |

| approaches | In the context of limits, the behavior of a function's output as the input gets arbitrarily close to a specific value. |

| function | A mathematical relationship that assigns exactly one output value to each input value of an independent variable. |

| limit | The value that a function approaches as the input approaches some value, which may or may not equal the function's value at that point. |

| limit notation | The symbolic representation of a limit, written as lim[x→c] f(x) = R, indicating that f(x) approaches R as x approaches c. |

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I write limit notation correctly?

Write limits exactly like this: lim[x→c] f(x) = L when f(x) can be made arbitrarily close to L as x approaches c (but x ≠ c). Use one-sided notation when needed: lim[x→c⁻] f(x) (left-hand) or lim[x→c⁺] f(x) (right-hand). Say the limit does not exist as “lim[x→c] f(x) does not exist” or “DNE” when the two one-sided limits differ or blow up. For limits at infinity use lim[x→∞] f(x) = L (horizontal asymptote) and for vertical asymptotes write lim[x→c] f(x) = ±∞. Common shorthand: lim[x→c] f(x) = L, lim[x→c⁺] f(x) = L+, lim[x→c⁻] f(x) = L−. Don’t confuse f(c) with the limit; continuity at c means both exist and equal. The AP exam won’t test epsilon–delta (CED), but it will expect correct notation and interpretation. For more examples and practice, see the Topic 1.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/defining-limits-using-limit-notation/study-guide/NWqOTUfp5qyR2oC2s4GD), Unit 1 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1) and tons of practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

What does lim x→c f(x) = R actually mean?

lim x→c f(x) = R means: as x gets arbitrarily close to c (from either side)—but x need not equal c—the outputs f(x) get arbitrarily close to the single real number R. Practically, you can make f(x) as near to R as you want by taking x sufficiently near c. This says nothing about f(c) itself: f(c) might equal R, be different, or be undefined (removable discontinuity). If the left- and right-hand limits differ, the two-sided limit does not exist. The formal epsilon–delta definition isn’t tested on AP (CED exclusion), but you should be comfortable interpreting limits analytically, graphically, and numerically and recognizing indeterminate forms like 0/0. For a quick review, see the Topic 1.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/defining-limits-using-limit-notation/study-guide/NWqOTUfp5qyR2oC2s4GD) and try practice problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

When do I use the arrow notation vs equals sign in limits?

Use the arrow (→) whenever you mean “x is approaching c”—it shows a limiting process. For example write lim_{x→c} f(x) = L to mean “as x gets arbitrarily close to c (but not equal to c), f(x) approaches L.” Use one-sided arrows for one-sided limits: lim_{x→c⁻} or lim_{x→c⁺}. Use x→∞ (or x→−∞) when talking about limits at infinity. Use the equals sign (=) only to state the result of that limit (or to equate expressions). So you combine them: lim_{x→c} f(x) = L. If the limit doesn’t exist, write lim_{x→c} f(x) does not exist (DNE) or say = ∞/−∞ for an infinite limit. This is exactly the EK LIM-1.A notation AP expects—get the arrow right to show the process, and the equals sign to state the value. For more examples and practice, see the Topic 1.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/defining-limits-using-limit-notation/study-guide/NWqOTUfp5qyR2oC2s4GD) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

I'm confused about what "approaches" means - does x ever equal c?

Short answer: "Approaches" means x gets arbitrarily close to c but does not have to equal c. The limit lim[x→c] f(x) describes the values of f(x) as x takes values near c (from both sides, unless you specify a one-sided limit). Whether f(c) exists or what f(c) equals is irrelevant to the limit. Example: f(x) = (x^2 − 1)/(x − 1) simplifies to x + 1 for x ≠ 1. As x approaches 1 (x ≠ 1), f(x) → 2, so lim[x→1] f(x) = 2 even though f(1) is undefined. If f(1) were defined as 2, the discontinuity would be removable. This is exactly what EK LIM-1.A.1 says: make f(x) arbitrarily close to R by taking x sufficiently close to c (but not equal to c). The formal epsilon-delta idea may be shown in class but isn’t tested on the AP exam. For a short study refresher, see the Topic 1.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/defining-limits-using-limit-notation/study-guide/NWqOTUfp5qyR2oC2s4GD) and more practice at the Unit 1 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1) or practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

How do I know if a limit exists or not?

A limit lim[x→c] f(x) exists (and equals a real number R) exactly when both one-sided limits exist and equal the same finite R: lim[x→c⁻] f(x) = lim[x→c⁺] f(x) = R. Practically check three ways (CED LIM-1.B): - Graphically: left and right approach same y-value. - Numerically: table values approaching c from both sides trend to the same number. - Analytically: simplify/algebraically evaluate the expression (use limit laws; 0/0 is an indeterminate form that needs algebraic work—could be removable). If one-sided limits differ (jump), or either side blows up to ±∞ (infinite limit/vertical asymptote), or values oscillate without settling, the limit does not exist. The formal ε–δ definition isn't required for the AP exam (CED note), but understanding one-sided agreement is key. For more examples and practice, see the Topic 1.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/defining-limits-using-limit-notation/study-guide/NWqOTUfp5qyR2oC2s4GD) and lots of practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

What's the difference between the limit existing and the function being defined at that point?

They’re different questions. The limit lim[x→c] f(x) asks what values f(x) gets arbitrarily close to as x approaches c (but x ≠ c). It depends only on values near c, not the value at c itself (EK LIM-1.A). Whether f(c) is defined asks whether the function actually has a value at that single point. Quick consequences: - Limit exists but f(c) not defined (or defined differently): removable discontinuity (a “hole”). Example: f(x) = (x^2−1)/(x−1) has lim[x→1] f(x)=2, but if f(1) is undefined or f(1)=5, the limit still exists. - Limit exists and equals f(c): function is continuous at c. - Limit does not exist: left- and right-hand limits differ, or it blows up (infinite), or oscillates—then continuity fails regardless of f(c). For AP exam focus: be able to state limits using correct notation, check one-sided limits, and identify removable/jump/infinite discontinuities (see the Topic 1.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/defining-limits-using-limit-notation/study-guide/NWqOTUfp5qyR2oC2s4GD) and Unit 1 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1)). For extra practice, try problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

Can someone explain step by step how to read limit notation?

Think of limit notation as a compact sentence about what f(x) does as x gets close to some value. Step-by-step reading: - lim[x→c] f(x) = L means “as x approaches c (but x need not equal c), f(x) approaches the number L.” This matches EK LIM-1.A.1: f(x) can be made arbitrarily close to L by taking x sufficiently close to c. - lim[x→c⁻] f(x) and lim[x→c⁺] f(x] are left- and right-hand limits (one-sided limits). The two one-sided limits must equal for the two-sided limit to exist. - lim[x→∞] f(x) = L means f(x) approaches L as x grows without bound; lim[x→c] f(x) = ∞ describes an infinite limit/vertical asymptote. - If the expression gives 0/0 on substitution, it’s an indeterminate form—you must algebraically simplify or use other methods. - If the limit equals a finite value even when f(c) is undefined, that’s a removable discontinuity. For practice and AP-aligned review see the Topic 1.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/defining-limits-using-limit-notation/study-guide/NWqOTUfp5qyR2oC2s4GD) and more problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus). Remember: AP won’t ask epsilon-delta formally.

What does it mean when they say f(x) can be made "arbitrarily close" to R?

"Arbitrarily close" means you can make f(x) as near to the number R as you want by choosing x values sufficiently near c (but not equal to c). Practically: pick any tiny distance ε > 0 (like 0.1, 0.001, or 10^-6) and there exists some interval around c (except c itself) so that whenever x is inside that interval, |f(x) − R| < ε. So no matter how small a tolerance you demand, f(x) can be forced inside that tolerance by taking x close enough to c. This is the informal idea behind the limit statement lim[x→c] f(x) = R in the CED (EK LIM-1.A.1). AP won’t ask you to do full epsilon–delta proofs (that’s excluded), but understanding "arbitrarily close" helps you read and use limit notation and decide whether a limit exists. For more on this topic, see the Topic 1.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/defining-limits-using-limit-notation/study-guide/NWqOTUfp5qyR2oC2s4GD) and try practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

How do I write the limit of x squared as x approaches 3?

You write it exactly using limit notation and evaluate it: lim_{x→3} x^2 = 9. Why: polynomials are continuous everywhere (CED EK LIM-1.A), so the limit as x approaches 3 equals the function value f(3) = 3^2 = 9. You could also note the formal form from the CED: lim[x→c] f(x) = R when f(x) gets arbitrarily close to R as x→c (here c = 3 and R = 9). If you want more practice with limit notation and examples on the AP scope, check the Topic 1.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/defining-limits-using-limit-notation/study-guide/NWqOTUfp5qyR2oC2s4GD) and the Unit 1 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1). For extra problems, use the practice problem bank (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

I don't understand why we write x→c instead of x=c in limits.

Because a limit describes what f(x) gets close to as x moves near c—not what f(c) actually is—we write x → c (x approaches c) instead of x = c (x equals c). The CED’s EK LIM-1.A says the limit L exists if f(x) can be made arbitrarily close to L by taking x sufficiently close to c (but not equal to c). That “but not equal” is the key: f(c) might be undefined or a different number (a removable discontinuity), yet the nearby values of f(x) still settle at the same L. Example: (x^2 − 1)/(x − 1) has limit 2 as x → 1 even though the expression is undefined at x = 1 (0/0 indeterminate). Using x = c would force you to evaluate f(c), which misses the idea of approaching from both sides (or one-sided limits) and breaks cases with holes or jumps. For more examples and AP-aligned practice, see the Topic 1.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/defining-limits-using-limit-notation/study-guide/NWqOTUfp5qyR2oC2s4GD) and the practice question bank (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

When does a limit not exist and how do I show that?

A limit does not exist (DNE) when f(x) doesn’t approach a single real number as x→c. Common reasons and how to show each: - Left/right disagreement (jump): lim[x→c−] f(x) ≠ lim[x→c+] f(x). Compute both one-sided limits; if they differ (e.g., 2 vs. 5) the two-sided limit DNE. - Infinite/vertical asymptote: one or both one-sided limits are ±∞. Show that values grow without bound (e.g., 1/(x−c) → ±∞). - Oscillation: values keep oscillating (no settle), e.g., f(x)=sin(1/x) as x→0. Show subsequences with different limits. - No approach because function undefined around c or wild behavior: exhibit sequences x_n→c giving different f(x_n) limits. On the AP exam you won’t need epsilon–delta (CED excludes it), but you must use analytic, numeric, or graphical evidence (compute one-sided limits, algebraic simplification, or show blow-up/oscillation). For quick review, see the Topic 1.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/defining-limits-using-limit-notation/study-guide/NWqOTUfp5qyR2oC2s4GD) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

What's the formula for writing limits when x approaches infinity?

When x grows without bound you use the "limit at infinity" notation. The basic formulas: - If f(x) approaches a finite real number L as x → ∞: lim_{x→∞} f(x) = L (This describes a horizontal asymptote y = L.) - If f(x) grows without bound: lim_{x→∞} f(x) = ∞ or lim_{x→∞} f(x) = −∞ (This says the function increases/decreases without bound.) - You can also write limits as x → −∞ the same way: lim_{x→−∞} f(x) = L, ∞, or −∞. On the AP exam you should use this analytic notation (CED LIM-1.A, LIM-1.B). For more examples and practice, see the Topic 1.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/defining-limits-using-limit-notation/study-guide/NWqOTUfp5qyR2oC2s4GD) and the Unit 1 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1).

How do I interpret limits from a graph vs from an equation?

From a graph: read the behavior of f(x) as x approaches c from the left and right. Find the left-hand limit lim[x→c−] f(x) and the right-hand limit lim[x→c+] f(x]. If those agree and are finite, lim[x→c] f(x) equals that common value. If they differ, the limit does not exist (jump). If values blow up to ±∞, you have an infinite limit/vertical asymptote. Remember the actual value f(c) can be different (removable discontinuity)—the limit depends on nearby x, not f(c). From an equation: simplify or manipulate the expression (factor, cancel, use algebraic limit laws) and evaluate the resulting expression as x→c. If you get 0/0, use algebraic simplification (or known limits) to resolve an indeterminate form; if denominator →0 and numerator→nonzero, you likely have ±∞. AP tip: always check one-sided limits for points where the graph or formula changes (piecewise). The CED focuses on interpreting limits graphically and analytically (LIM-1.A, LIM-1.B). For a focused review see the Topic 1.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/defining-limits-using-limit-notation/study-guide/NWqOTUfp5qyR2oC2s4GD) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

Why do we care about limits if the function might not even be defined at that point?

Good question—we care about limits because they describe the behavior of a function near a point, not just the value at the point. The CED definition (LIM-1.A.1) says lim[x→c] f(x) = R means f(x) can be made arbitrarily close to R by taking x near c (but x ≠ c). That lets us: - talk about instantaneous behavior (needed for the derivative) even if f(c) is undefined or different, - identify removable discontinuities (limit exists but f(c) is undefined or mismatched) versus jump/infinite ones, - find vertical asymptotes or limits at infinity that describe end behavior. On the AP exam you’ll use limits analytically, graphically, and numerically (LIM-1.B.1). The epsilon-delta formalism isn’t required for AP, so focus on understanding one-sided limits, 0/0 indeterminate forms, and algebraic techniques to evaluate limits. For a focused review, see the Topic 1.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/defining-limits-using-limit-notation/study-guide/NWqOTUfp5qyR2oC2s4GD) and try practice problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).

What are all the different ways to express the same limit?

You can express the same limit in several equivalent ways—use whichever representation makes the idea or the problem easiest: - Analytic (standard) notation: lim[x→c] f(x) = L (if you mean both sides). - One-sided notation: lim[x→c⁻] f(x) = L (left) or lim[x→c⁺] f(x) = L (right). Useful when sides differ. - Infinite/at-infinity forms: lim[x→c] f(x) = ∞ or lim[x→∞] f(x) = L (behavior near vertical/horizontal asymptotes). - Algebraic equation: say “f(x) approaches L as x approaches c,” or write an equivalent simplified expression whose ordinary substitution gives L (useful when you cancel factors). - Numerical (table): list x-values approaching c with corresponding f(x) values that approach L. - Graphical: show the graph’s y-values approaching L as x gets near c (but not necessarily f(c)). - Sequence form: for any sequence x_n → c (x_n ≠ c), f(x_n) → L—another precise analytic way. AP exams ask you to connect these representations (LIM-1.B). For a quick study refresher check the Topic 1.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-calculus/unit-1/defining-limits-using-limit-notation/study-guide/NWqOTUfp5qyR2oC2s4GD) and try practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-calculus).