The big idea of this section and the rest of the math-y part of probability: The likelihood of a random event can be quantified!

That being said, we'll learn how to (1) calculate probabilities for events and their complements and (2) interpret probabilities for events. Not too daunting for an introductory dive into the basics of probability, huh?

Basic Probability Rules

A probability model is a mathematical representation of a chance process that is used to describe the likelihood of different outcomes occurring. It consists of two main components: a list of all possible outcomes and the probability of each outcome occurring.

The sample space is a list of all the possible outcomes of a chance process, such as flipping a coin or rolling a die. For example, the sample space for flipping a coin might be {heads, tails}, while the sample space for rolling a die might be {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}.

Using this model, probabilities are usually expressed as fractions or decimals. For example, the probability of flipping heads when flipping a coin is 0.5, and the probability of rolling a 6 when rolling a die is 1/6.

A probability model is a description of some chance process that is made up of two portions: a list of all possible outcomes and the probability for each outcome. The list of all possible outcomes is called a sample space.

Rule 1: Equally Likely Probability

If all outcomes in a sample space are equally likely, the probability that event A occurs can be calculated by dividing the number of outcomes in event A by the total number of outcomes in the sample space. This is known as the classical definition of probability.

P(A) = number of outcomes in event A / total number of outcomes in the sample space.

For example, if we have a sample space of 6 outcomes (such as rolling a die), and event A consists of 3 of those outcomes (such as rolling a 1, 2, or 3), the probability of event A occurring would be 3/6, or 0.5. This is because there are 3 outcomes in event A, and there are a total of 6 outcomes in the sample space, so the probability of event A occurring is 3/6.

Rule 2: 0 < Probability < 1

Probabilities are always expressed as numbers between 0 and 1, inclusive, with a probability of 0 indicating that an event is impossible, a probability of 1 indicating that an event is certain to occur, and probabilities between 0 and 1 indicating that an event is possible but not certain.

For example, the probability of flipping heads when flipping a coin is 0.5, the probability of rolling a 6 when rolling a die is 1/6, and the probability of drawing an ace from a deck of cards is 4/52. These probabilities all fall between 0 and 1, indicating that these events are possible but not certain to occur.

When you do your math, getting probability values like -0.82 and 1.63 is an instant red flag! The good thing with this rule is that you can immediately sense something's wrong should you get such answers and immediately troubleshoot.

Rule 3: P(all outcomes) = 1!

All possible outcomes MUST add up to 1. That's right! The probabilities of all possible outcomes in a sample space add up to 1. This is because the probability of an event occurring is a measure of the likelihood of that event occurring, and the probability of all possible events occurring must be 1 (since one of those events must occur).

For example, consider the probability of rolling a die. There are six possible outcomes (rolling a 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6), and the probability of each outcome occurring is 1/6. If we add up the probabilities of all six outcomes, we get:

1/6 + 1/6 + 1/6 + 1/6 + 1/6 + 1/6 = 6/6 = 1

This demonstrates that the probabilities of all possible outcomes (rolling a 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6) add up to 1, as expected.

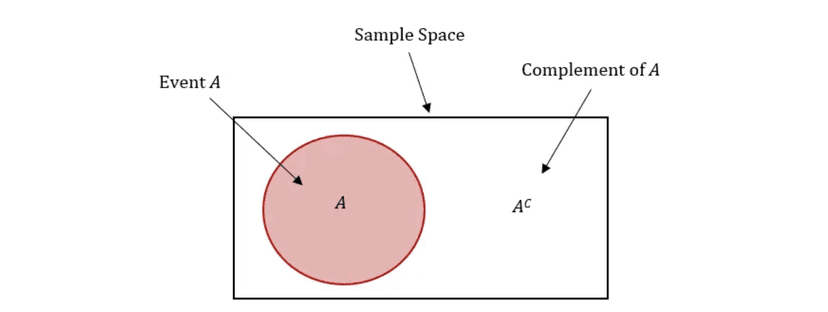

Rule 4: Complements

The probability of the complement of an event (also known as the inverse or opposite of an event) is equal to 1 minus the probability of the event occurring. This is because the probability of an event occurring and the probability of the event not occurring must add up to 1, since one of those two events must occur.

For example, consider the probability of flipping heads when flipping a coin. The probability of flipping heads is 0.5, so the probability of flipping tails (which is the complement of flipping heads) is 1 - 0.5 = 0.5. Similarly, if the probability of rolling a 6 when rolling a die is 1/6, the probability of rolling any number other than a 6 (which is the complement of rolling a 6) is 1 - 1/6 = 5/6.

The College Board sometimes refers to the complement as E' or E^c (i.e. not E) = 1 - P(E). You'll most likely have to use this rule when problems ask for probability values mentioninig "at least ___" or "at most ___."

As you go through more sections, we'll add onto this growing list of probability rules.

Probabilities and Context

Be sure to know how to interpret the probability you calculate. Remember to use words involving context!

Example

A company that manufactures car parts wants to understand the quality of their production process. To do this, they decide to sample a random selection of 100 car parts and test them for defects. The results of the testing show that 20 parts are defective and 80 parts are non-defective.

Based on the results of the testing, the company makes the following conclusions:

- The probability that a randomly selected car part is defective is 20%.

- The probability that a randomly selected car part is non-defective is 80%.

- There is a 20% chance that a randomly selected car part will be defective.

- There is an 80% chance that a randomly selected car part will be non-defective.

Write a brief summary explaining the company's conclusions and the statistical evidence that supports them.

Answer

The company concludes that the probability that a randomly selected car part is defective is 20%, and that the probability that a randomly selected car part is non-defective is 80%, based on the statistical evidence provided in the results of the testing. The company also concludes that there is a 20% chance that a randomly selected car part will be defective, and an 80% chance that a randomly selected car part will be non-defective.

The statistical evidence that supports these conclusions is the fact that 20 out of 100 car parts were defective, and 80 out of 100 car parts were non-defective. This means that the probability of a randomly selected car part being defective is 20/100, or 20%, and the probability of a randomly selected car part being non-defective is 80/100, or 80%.

🎥Watch: AP Stats - Probability Rules and Random Variables

Vocabulary

The following words are mentioned explicitly in the College Board Course and Exam Description for this topic.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| complement of an event | The set of all outcomes in the sample space that are not in event E, denoted E' or E^C, representing 'not E'. |

| equally likely | A condition where all outcomes in a sample space have the same probability of occurring. |

| event | A collection of one or more outcomes from a random process. |

| long run | A large number of repetitions of a probability experiment where the relative frequency of an event approaches its true probability. |

| outcome | The result of a single trial of a random process. |

| probability | The likelihood or chance that a particular outcome or event will occur, expressed as a value between 0 and 1. |

| random process | A process that generates results determined by chance, where the outcome cannot be predicted with certainty in advance. |

| relative frequency | The proportion of observations in a category, expressed as a decimal, fraction, or percentage of the total. |

| sample space | The set of all possible non-overlapping outcomes of a random process. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What's the formula for calculating probability when all outcomes are equally likely?

If every outcome in the sample space is equally likely, the probability of an event E is P(E) = (number of outcomes in E) / (total number of outcomes in the sample space). So if a fair 6-sided die is rolled, P(rolling an even number) = 3/6 = 1/2. Remember this is the CED’s definition for “theoretical probability” when outcomes are equally likely (VAR-4.A.2). Probabilities always lie between 0 and 1, and the complement rule is useful: P(E') = 1 − P(E) (VAR-4.A.3–4). For more AP-focused review and quick examples on Topic 4.3, check the Fiveable topic study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/intro-probability/study-guide/gfnBWfyMANOxF3vWLrbA). If you want more practice problems, Fiveable has lots at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I find the sample space for rolling two dice?

The sample space is the set of all possible outcomes. For two fair six-sided dice you usually treat outcomes as ordered pairs (die1, die2). So the sample space S = {(1,1),(1,2),…,(1,6),(2,1),(2,2),…,(6,6)}—36 equally likely outcomes. Use VAR-4.A.2: if outcomes are equally likely, P(E) = (# outcomes in E)/36. Example: the event “sum = 7” has outcomes {(1,6),(2,5),(3,4),(4,3),(5,2),(6,1)} so P(sum=7)=6/36=1/6. Remember probabilities are between 0 and 1 and complements follow P(E^c)=1−P(E) (VAR-4.A.3–4). For more examples and AP-style practice on Topic 4.3, check the Fiveable study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/intro-probability/study-guide/gfnBWfyMANOxF3vWLrbA) and try practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

When do I use the complement rule vs just calculating probability directly?

Use the complement rule when it’s easier to count “not E” than E itself. By VAR-4.A.4, P(Eᶜ) = 1 − P(E). So if E is “at least one success” or “at least k,” it’s often simpler to compute P(no successes) and subtract from 1 (e.g., P(at least one head in 5 flips) = 1 − P(0 heads)). Use direct calculation when the event E has few equally likely outcomes or a straightforward formula (like a single binomial term). Always check the sample space and whether outcomes are equally likely (VAR-4.A.1–2). On the exam, pick the method that minimizes algebra and errors—complement for “at least one” or “at least k” problems, direct for single-outcome probabilities. Want more examples and practice? See the Topic 4.3 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/intro-probability/study-guide/gfnBWfyMANOxF3vWLrbA), the Unit 4 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4), and lots of practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What's the difference between an event and a sample space?

The sample space is the set of all possible non-overlapping outcomes of a random process (CED VAR-4.A.1). An event is any subset of that sample space—one or more outcomes you care about. Example: toss two coins. The sample space S = {HH, HT, TH, TT}. An event E might be “exactly one head” = {HT, TH}. Probability of an event is #outcomes in E divided by #outcomes in S when outcomes are equally likely (VAR-4.A.2), so P(E)=2/4=0.5. Remember probabilities are between 0 and 1 (VAR-4.A.3), and the complement rule says P(E′)=1−P(E) (VAR-4.A.4). For AP exam practice, study these definitions and simple computations—they show up in Topic 4.3 and are covered in the Fiveable Topic 4.3 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/intro-probability/study-guide/gfnBWfyMANOxF3vWLrbA). For extra practice, try problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

I don't understand what "equally likely outcomes" means - can someone explain?

“Equally likely outcomes” means every outcome in the sample space has the same chance of happening. If that’s true, you can use the simple formula from the CED: P(E) = (number of outcomes in E) / (total number of outcomes) (VAR-4.A.2). Examples: a fair coin has two equally likely outcomes {H, T} so P(H) = 1/2; a fair six-sided die has six equally likely outcomes so P(rolling a 4) = 1/6; a spinner divided into four equal wedges gives P(landing on a given wedge) = 1/4. If outcomes aren’t equally likely (biased coin, uneven spinner), you can’t use the simple count formula—you need theoretical or empirical probabilities instead (VAR-4.B.1). Remember the complement rule: P(E') = 1 − P(E) (VAR-4.A.4). For more practice and AP-aligned review, check the Topic 4.3 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/intro-probability/study-guide/gfnBWfyMANOxF3vWLrbA) and Unit 4 resources (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4).

How do I calculate P(E') if I know P(E)?

Use the complement rule: P(E′) = 1 − P(E). The complement E′ is “not E,” and since probabilities of all outcomes in the sample space sum to 1, whatever chance E happens plus whatever chance it doesn’t must equal 1 (CED VAR-4.A.4). Example: if P(E) = 0.65, then P(E′) = 1 − 0.65 = 0.35. If P(E) = 0, P(E′) = 1; if P(E) = 1, P(E′) = 0. Always check that 0 ≤ P(E) ≤ 1 first (CED VAR-4.A.3). This is a basic AP Stats skill you should know for Topic 4.3 and for multiple-choice/free-response probability questions. For a quick refresher, see the Topic 4.3 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/intro-probability/study-guide/gfnBWfyMANOxF3vWLrbA) and practice lots of problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What does it mean when they say probability is between 0 and 1 inclusive?

Saying a probability is between 0 and 1 inclusive means any event’s chance is a number from 0 up to 1 (0 ≤ P(E) ≤ 1). 0 means the event is impossible (it can’t happen), 1 means it’s certain (it will happen), and numbers in between measure how likely it is (e.g., 0.25 = 25% chance). This is one of the basic probability axioms in the CED (VAR-4.A.3). If you know the sample space S, every event’s probability is a portion of S and the probabilities of all possible outcomes add to 1. Also remember the complement rule: P(E′) = 1 − P(E) (VAR-4.A.4). In repeatable situations you can interpret probabilities as long-run relative frequencies—if you repeat the random process many times, the proportion of times E occurs should approach P(E) (VAR-4.B.1). For a short refresher and practice on Topic 4.3, see the Fiveable study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/intro-probability/study-guide/gfnBWfyMANOxF3vWLrbA) and try problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I solve probability word problems step by step?

Step-by-step for any probability word problem (AP Stats style): 1. Read carefully and identify the random process, outcomes, and question (what event E are you finding?). 2. List the sample space S (all non-overlapping outcomes). Decide if outcomes are equally likely. (CED: VAR-4.A.1) 3. If equally likely, use P(E) = #(outcomes in E) / #(outcomes in S). If not, use given probabilities or a model (binomial, geometric, etc.). (CED: VAR-4.A.2) 4. Check complements: sometimes P(E′)=1−P(E) is easier. (CED: VAR-4.A.4) 5. For repeated trials, consider binomial rules: P(X = k) = C(n,k) p^k (1−p)^(n−k). Verify conditions (independence, fixed n, same p). 6. Interpret answer in context and, if relevant, mention long-run frequency (law of large numbers). (CED: VAR-4.B.1) 7. Double-check values, units, and that probabilities are between 0 and 1. (CED: VAR-4.A.3) Want worked examples and practice? See the Topic 4.3 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/intro-probability/study-guide/gfnBWfyMANOxF3vWLrbA) and tons of practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

Why is the probability of the complement equal to 1 minus the original probability?

Think of the sample space S as all possible, non-overlapping outcomes—something must happen, so P(S)=1 (VAR-4.A.1 and VAR-4.A.3). Any event E and its complement E^C (not E) are disjoint (they share no outcomes) and together are collectively exhaustive (E ∪ E^C = S). By the addition rule for disjoint events, P(E) + P(E^C) = P(S) = 1. Rearranging gives P(E^C) = 1 − P(E) (VAR-4.A.4). Quick example: roll a fair six-sided die. E = “roll a 4” has P(E)=1/6, so E^C = “not 4” has P(E^C)=5/6 = 1 − 1/6. This complement rule is useful on the exam—sometimes it’s easier to find P(E^C) and subtract from 1 (Skill 3.A). For a refresher, see the Topic 4.3 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/intro-probability/study-guide/gfnBWfyMANOxF3vWLrbA) and try practice problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What's the difference between theoretical probability and relative frequency?

Theoretical probability is what a probability model predicts from logic or symmetry: P(heads) = 1/2 for a fair coin because there are 1 favorable outcome out of 2 equally likely outcomes (VAR-4.A.2). Relative frequency (empirical probability) is what you actually observe when you repeat a random process: if you flip a coin 100 times and get 56 heads, the relative frequency of heads is 56/100 = 0.56. The CED says probabilities in repeatable situations can be interpreted as long-run relative frequencies (VAR-4.B.1): as you repeat the process many times, the relative frequency tends to the theoretical probability (law of large numbers). For AP exam work, know both: use theory when outcomes are equally likely, and use relative frequency or simulation when you can’t assume equally likely outcomes. For a quick review, see the Topic 4.3 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/intro-probability/study-guide/gfnBWfyMANOxF3vWLrbA) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

I'm confused about when outcomes are overlapping vs non-overlapping - how do I tell?

Think: can both events happen at the same time? If yes → outcomes overlap; if no → non-overlapping (disjoint). - Non-overlapping (disjoint): A ∩ B = ∅. They have no outcomes in common, so P(A ∪ B) = P(A) + P(B). Example: "roll a 1" and "roll a 2" on one die—cannot both occur. The CED even states the sample space is made of non-overlapping outcomes (VAR-4.A.1). - Overlapping: A ∩ B ≠ ∅. They share outcomes, so you must subtract the intersection: P(A ∪ B) = P(A) + P(B) − P(A ∩ B). Example: on a die, A = even {2,4,6}, B = multiple of 3 {3,6} overlap at {6}. Quick checks for tests/problems: list outcomes in the sample space (equally likely helps), see if any outcome appears in both events. For more practice and examples, see the Topic 4.3 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/intro-probability/study-guide/gfnBWfyMANOxF3vWLrbA) and more practice questions (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I interpret what a probability of 0.3 actually means in real life?

A probability of 0.3 means there’s a 30% chance the event happens—or, more precisely for AP Stats, you expect it to happen about 30% of the time in the long run if you repeat the random process many times (that’s the relative-frequency interpretation from VAR-4.B). It’s a number between 0 and 1 (VAR-4.A.3), so the complement (not happening) has probability 0.7 (VAR-4.A.4). Concrete: if P(rain tomorrow)=0.3, you shouldn’t say “it won’t rain,” you should say “if we look at many similar days, about 30% would have rain.” Same for drawing a red marble or a student answering correctly on a random multiple-choice question. The law of large numbers explains why the long-run frequency settles near 0.3 as trials increase—useful to know for AP exam interpretations and free-response wording. For more examples and practice on Topic 4.3, see the Fiveable study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/intro-probability/study-guide/gfnBWfyMANOxF3vWLrbA) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What's the formula for finding the total number of outcomes in a sample space?

The total number of outcomes in a sample space depends on the situation, but the basic formulas you should know for AP Stats are: - Fundamental Counting Principle (product rule): if a process has stages with m, n, … choices, total outcomes = m × n × … - Permutations (order matters): number of ways to arrange k from n = nPk = n! / (n − k)! - Combinations (order doesn’t matter): number of ways to choose k from n = nCk = n! / [k!(n − k)!] - If all outcomes are equally likely, probability of event E = (number of outcomes in E) / (total number of outcomes in sample space), as in the CED (VAR-4.A.2). Use these depending on whether order matters and whether repeats are allowed. For more examples and practice tied to Topic 4.3, check the Fiveable study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/intro-probability/study-guide/gfnBWfyMANOxF3vWLrbA) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I know if I should use the complement or calculate the probability normally?

Use the complement when the event you want is “not” something that’s easier to count than the event itself. By the complement rule (VAR-4.A.4) P(E^C) = 1 − P(E). Ask: is E or E^C simpler to describe/count? Quick checklist: - If E = “at least one …” (or “one or more”), compute P(E) = 1 − P(none). Example: P(at least one head in 4 fair flips) = 1 − P(0 heads) = 1 − (1/2)^4. - If E has many possible outcomes but E^C has few, use the complement. - If outcomes are equally likely, use counting (VAR-4.A.2) for whichever set is smaller. - If events are disjoint/collectively exhaustive, complements pair naturally (use P(A ∪ A^C)=1). For AP: show you know the sample space and justify why you used the complement (tie to VAR-4.A and Skill 3.A). For extra practice and examples see the Topic 4.3 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/intro-probability/study-guide/gfnBWfyMANOxF3vWLrbA) and more practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

When they say "long run" for relative frequency, what does that actually mean?

“Long run” means what happens after you repeat a random process many times—not just a few tries, but lots and lots. In the relative-frequency interpretation (CED VAR-4.B.1) the probability of an event is the proportion of times that event occurs in repeated, independent trials as the number of trials grows large. Practically that means if you flip a fair coin 10 times you might get 7 heads, but if you flip it 10,000 or 100,000 times the fraction of heads should get very close to 0.5 (this is the Law of Large Numbers). On the AP, when you’re asked to “interpret probability,” tie it to long-run relative frequency—say “in repeated trials, the average proportion will approach P(E).” For a quick review, see the Topic 4.3 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/intro-probability/study-guide/gfnBWfyMANOxF3vWLrbA). For more practice, try the problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).