A simulation is a useful tool in statistics that allows us to anticipate patterns in data by generating synthetic data based on certain assumptions or models. Simulations can be used to explore the behavior of a statistical model or process over a range of scenarios, and can provide insights into the likely patterns that will emerge in real-world data. In this section, we'll make sure you know how to conduct or come up with a simulation with several trials and calculate probabilities from the resulting data.

Simulation Time!

Simulations are examples of random processes, which generate results that are determined by chance. These processes yield results, also known as outcomes, from trials. Combining a bunch of these overall outcomes leads to what we call an event.

One example that could clarify the difference between an outcome and an event is the example of die rolling:

- Rolling a particular value on a six-sided number cube is one of six possible outcomes, as in getting a 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, OR 6, illustrates an outcome.

- When rolling two six-sided number cubes, an event would be a sum of seven. The corresponding collection of outcomes would be (1, 6), (2, 5), (3, 4), (4, 3), (5, 2), and (6, 1), where the ordered pairs indicate (face value on one cube, face value on the other cube).

Where do simulations come in, then?

Large Numbers Have Laws, Too!

As a refresher, probability is defined as a numerical outcome between 0 and 1 of a chance process. Here's the new idea: probability also describes the proportion of times the outcome would occur in a very long series of repetitions. Chance behavior is unpredictable in the short run but has a regular and predictable pattern in the long run, which is described by the law of large numbers.

The law of large numbers states that simulated (empirical) probabilities tend to get closer to the true probability as the number of trials increases.

Here are a couple of applications of the law in common probabilistic examples:

- Flipping a coin: If you flip a coin a large number of times, the law of large numbers states that the simulated probability of getting heads will tend to approach the true probability of getting heads (which is 0.5) as the number of flips increases. For example, if you flip a coin 10 times and get 6 heads, the simulated probability of getting heads is 0.6. If you flip the coin 100 times and get 50 heads, the simulated probability of getting heads is 0.5. As you can see, the simulated probability gets closer to the true probability as the number of flips increases.

- Rolling a die: The law of large numbers can also be applied to the rolling of a die. If you roll a die a large number of times, the simulated probability of rolling a particular number (such as a 6) will tend to approach the true probability of rolling that number (which is 1/6) as the number of rolls increases.

- Spinning a roulette wheel: The law of large numbers can also be applied to the spinning of a roulette wheel. If you spin the wheel a large number of times, the simulated probability of the ball landing on a particular number (such as 25) will tend to approach the true probability of the ball landing on that number (which is 1/38) as the number of spins increases.

Rinsing & Repeating

To give a simpler definition of the section opener above, a simulation is a way to model random events, such that simulated outcomes closely match real-world outcomes. All possible outcomes are associated with a value to be determined by chance.

In a simulation, all possible outcomes are associated with a value that is determined by chance. For example, in a simulation of rolling a die, there are six possible outcomes (rolling a 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6), and each outcome is associated with a certain probability (1/6 for each outcome).

To conduct a simulation, we typically repeat the process a large number of times (known as trials) and record the counts of the simulated outcomes. We can then use these counts to calculate the simulated probability of each outcome and compare these probabilities to the true probabilities that we expect to see in the real world.

Here's the process of conducting a simulation in bullet point terms:

- Describe how to use a chance device to imitate one trial (repetition) of the simulation. State what you’ll record at the end of each trial.

- Perform many trials of the simulation.

- Use the results of your simulation to answer the question of interest. 🎥 Watch: AP Stats - Probability Rules and Random Variables

Practice Problem

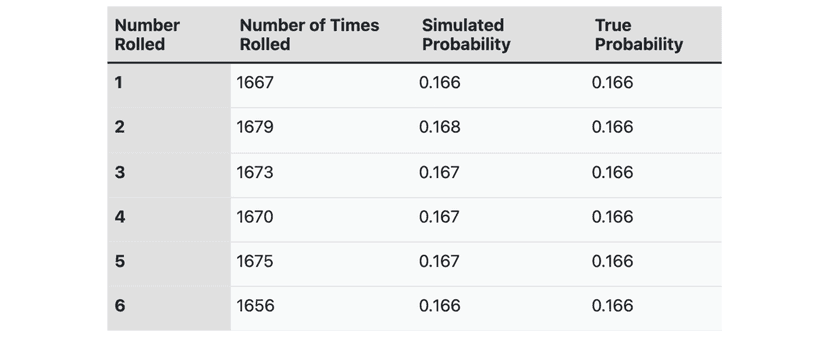

A statistics professor is interested in studying the behavior of a six-sided die, and decides to conduct a simulation to explore the probabilities of rolling different numbers. To do this, the professor sets up a computer program to simulate the rolling of a die 10,000 times, and records the outcomes of each roll.

The professor then calculates the simulated probability of rolling each number, and compares these probabilities to the true probability of rolling each number (which is 1/6 for each number). The results of the simulation are shown in the table below:

Based on the results of the simulation, the professor makes the following conclusions:

- The simulated probabilities of rolling each number are very close to the true probabilities.

- The simulated probabilities of rolling each number are not significantly different from one another.

Write a brief summary explaining the professor's conclusions and the statistical evidence that supports them.

Answer

The professor concludes that the simulated probabilities of rolling each number are very close to the true probabilities, and that the simulated probabilities of rolling each number are not significantly different from one another, based on the statistical evidence provided in the simulation results.

One piece of evidence that supports these conclusions is the fact that the simulated probabilities of rolling each number are all very close to the true probability of 1/6. This suggests that the simulation is producing outcomes that are consistent with the probabilities that we would expect to see in the real world.

Another piece of evidence that supports these conclusions is the fact that the simulated probabilities of rolling each number are not significantly different from one another. This suggests that the simulation is not producing outcomes that are biased towards any particular number, and that all of the numbers are equally likely to be rolled.

Overall, the statistical evidence suggests that the simulation is producing outcomes that are consistent with the true probabilities of rolling each number, and that the outcomes are not significantly different from one another. This supports the professor's conclusions about the behavior of the die.

Vocabulary

The following words are mentioned explicitly in the College Board Course and Exam Description for this topic.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| event | A collection of one or more outcomes from a random process. |

| law of large numbers | The principle that simulated or empirical probabilities tend to get closer to the true probability as the number of trials increases. |

| outcome | The result of a single trial of a random process. |

| random process | A process that generates results determined by chance, where the outcome cannot be predicted with certainty in advance. |

| relative frequency | The proportion of observations in a category, expressed as a decimal, fraction, or percentage of the total. |

| simulation | A method of modeling random events so that simulated outcomes closely match real-world outcomes, used to estimate probabilities. |

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I set up a simulation to estimate probability?

Start by clearly defining the random process, one trial, and the event you want to estimate. Example: “pick 3 students; event = at least 2 like pizza.” Choose a way to randomize each trial (dice, cards, random number generator or calculator/binompdf/binomrnd) and decide whether sampling is with or without replacement (important—CED keywords: sampling with replacement). Map each possible outcome to a result (success/failure), run many trials (1000+ if you can), and record counts of successes and total trials. Estimate the probability as relative frequency = successes / trials. Use the law of large numbers: more trials → estimate closer to true probability. Report your setup (how you simulated), number of trials, and the estimate. For AP exam practice, know you may use a graphing calculator and should describe your simulation method clearly. For a step-by-step study guide, check Fiveable’s Topic 4.2 guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/estimating-probabilities-using-simulation/study-guide/ABwpnnUf4VCXeVbB9q72) and try practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What's the difference between an outcome and an event in probability?

An outcome is a single result from one trial of a random process (e.g., rolling a 6 on a six-sided cube, or the ordered pair (2,5) when you roll two cubes). An event is any collection of one or more outcomes that share a property you care about (e.g., “sum = 7” when rolling two cubes—that event contains the outcomes (1,6), (2,5), (3,4), (4,3), (5,2), (6,1)). On the AP Stats CED this distinction matters because simulation records individual outcomes across many trials, then uses the relative frequency of the event (counts of outcomes in that event ÷ total trials) to estimate its probability (UNC-2.A.2–A.5). As you run more trials, the law of large numbers says your simulated relative frequency will tend to the true probability (UNC-2.A.6). For a quick review on simulation and how to set up trials, check the Topic 4.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/estimating-probabilities-using-simulation/study-guide/ABwpnnUf4VCXeVbB9q72). If you want practice, Fiveable has lots of AP-style problems at https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics.

When do I use simulation instead of just calculating probability normally?

Use simulation when it’s hard or unreliable to get an exact probability by calculation. Good cases: complicated sample spaces (lots of outcomes or dependence), events defined by complicated rules, or when analytic formulas/approximations aren’t valid. Simulation models the random process, runs many trials, and uses the relative frequency of the event to estimate its probability (CED: UNC-2.A.4–2.A.5). When you can write a clean probability model (like a binomial, geometric, or simple conditional tree) you should calculate exactly. Use simulation when the math is messy or the assumptions for a standard model fail, or to check an approximation. Run lots of trials (hundreds to thousands) because of the law of large numbers—the estimate gets closer to the true probability as trials grow (UNC-2.A.6). On the AP exam you may be asked to describe or perform a simulation (use a random number generator, table, or calculator). For a focused guide, see the Topic 4.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/estimating-probabilities-using-simulation/study-guide/ABwpnnUf4VCXeVbB9q72). For extra practice, try problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

Can someone explain the law of large numbers step by step?

The law of large numbers (LLN) is simple: as you repeat a random process more times, the empirical (simulated) relative frequency of an event gets closer to its true probability. Step-by-step: 1. Pick a random process and an event (e.g., flip a biased coin; event = “heads”). 2. Run many independent trials and record outcomes (each trial = one run of the random process). 3. After n trials compute the relative frequency: #times event occurred ÷ n. 4. As n increases, that relative frequency tends to settle near the theoretical probability p (you’ll see less fluctuation). 5. Practically, doubling trials usually reduces random wiggle; extremely small n can be misleading. This is exactly why simulation (Monte Carlo) works for estimating probabilities (CED UNC-2.A.4–6). On the AP exam you may be asked to explain or run a simulation and note that larger trial counts give better estimates (Topic 4.2 study guide: https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/estimating-probabilities-using-simulation/study-guide/ABwpnnUf4VCXeVbB9q72). For more practice, check unit resources and 1000+ practice problems at Fiveable (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I know how many trials to run in my simulation?

You decide the number of trials by how precise and stable you need the estimated probability to be. By the law of large numbers (CED UNC-2.A.6), the relative frequency from your simulation will get closer to the true probability as you increase trials. Practically: run a pilot (e.g., 100–1,000 trials), look at the relative frequency, then keep increasing (to 1,000; 5,000; or 10,000) until the estimate stops changing much. Use more trials when the event is rare or when you need tighter accuracy. Always record counts and totals (UNC-2.A.4–5) and state that your estimate is empirical. For AP tasks, show your simulation method, number of trials, and final relative frequency—exam graders expect that clarity (Skill 3.A). For guidance and examples, see the Topic 4.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/estimating-probabilities-using-simulation/study-guide/ABwpnnUf4VCXeVbB9q72) and more Unit 4 resources (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4). For extra practice, try problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

I'm confused about relative frequency - how does it relate to probability?

Relative frequency is how often an outcome shows up in repeated trials—counts divided by total trials—and in simulation that fraction is your estimate of the probability. For example, if you simulate 1,000 flips and get 520 heads, the relative frequency of heads is 520/1000 = 0.52, so you’d estimate P(heads) ≈ 0.52. This idea is exactly UNC-2.A.5: simulated (empirical) relative frequencies estimate probabilities. The law of large numbers (UNC-2.A.6) says as you increase trials the relative frequency tends to get closer to the true probability, so 10,000 or 100,000 trials usually give a better estimate than 50. In practice you record outcome counts, compute relative frequencies, and use those as probability estimates for events (Skill 3.A). For more on simulation methods and examples, see the Topic 4.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/estimating-probabilities-using-simulation/study-guide/ABwpnnUf4VCXeVbB9q72) and practice lots of problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What's the formula for estimating probability using simulation results?

Use the relative frequency from your simulation. Formula: Estimated probability = (number of trials where the event occurred) / (total number of trials) So if your event happened 72 times in 200 simulated trials, estimate = 72/200 = 0.36. This is exactly what UNC-2.A.5 describes: simulated relative frequency approximates the true probability. By the law of large numbers (UNC-2.A.6), that estimate tends to get closer to the true probability as the number of trials increases, so run many trials for more stable estimates. On the AP exam you’ll often give probabilities as these empirical proportions from simulations (skill 3.A). For a refresher on simulation setup and examples, see the Topic 4.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/estimating-probabilities-using-simulation/study-guide/ABwpnnUf4VCXeVbB9q72). For extra practice, check the AP practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I assign random numbers to outcomes when doing a simulation?

Pick a clear list of all possible outcomes, then give each outcome a fair set of random numbers (equal-sized blocks) so your random-digit source picks outcomes with correct probabilities. Steps: 1. List outcomes and their probabilities (the event/sample space). 2. Choose your random-number source (table, calculator rand(), or random-digit generator). AP cares that the process models the random process and you record counts/relative frequencies. 3. Convert probabilities to equal-size blocks of digits. Example: if 3 outcomes have probs 0.50, 0.30, 0.20, use two-digit random numbers 00–49 → outcome A, 50–79 → B, 80–99 → C. For 25% each, give 00–24, 25–49, 50–74, 75–99. 4. Decide replacement vs. no replacement (affects mapping each trial). 5. Run many trials, record counts, and estimate probability by relative frequency (law of large numbers: more trials → closer to true probability). For practice and AP-aligned examples, check the Topic 4.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/estimating-probabilities-using-simulation/study-guide/ABwpnnUf4VCXeVbB9q72) and Unit 4 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4). For extra problems, use Fiveable practice (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

Why does my simulated probability keep changing every time I run it?

Your simulated probability changes because simulation is a random process—each trial is determined by chance (UNC-2.A.1–3). With a small number of trials you see lots of sampling variability: e.g., doing 50 trials one run might give 0.48 and another 0.56. The law of large numbers (UNC-2.A.6) says as you increase trials the relative frequency settles closer to the true probability—1000 or 10,000 trials will give a much more stable estimate than 50. Other causes of change: the random number generator (pseudo-random seed) and whether you’re sampling with or without replacement. On the AP exam you’ll be expected to estimate probabilities by simulation and explain this variability (Skill 3.A / Topic 4.2). For a quick refresher and examples, see the Topic 4.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/estimating-probabilities-using-simulation/study-guide/ABwpnnUf4VCXeVbB9q72). For extra practice problems, check the unit page (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4) and the practice bank (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

When rolling two dice what outcomes make up the event of getting a sum of 7?

An event is a collection of outcomes. For two fair six-sided dice, the event “sum = 7” is the set of ordered outcomes: (1, 6), (2, 5), (3, 4), (4, 3), (5, 2), (6, 1). There are 6 favorable ordered pairs out of 36 total ordered outcomes, so the theoretical probability is 6/36 = 1/6. If you’re estimating this with simulation (UNC-2.A), you’d model each trial as a random ordered pair, record how often the sum is 7, and use the relative frequency as your estimate. By the law of large numbers (UNC-2.A.6), your simulated relative frequency should approach 1/6 as the number of trials grows. For a quick review of simulation ideas for AP Stats, see the Topic 4.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/estimating-probabilities-using-simulation/study-guide/ABwpnnUf4VCXeVbB9q72). For more practice, check unit resources (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4) and the full practice question bank (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I use my calculator to generate random numbers for probability simulations?

Most graphing calculators can make pseudo-random numbers you can use to simulate trials. Quick steps for a TI-84/83 (common on the AP): - Get a random 0–1: rand( ) (MATH → PRB → rand). Use rand( ) < p to simulate a success with probability p (it returns 1 if true, 0 if false).

- Get random integers: randInt(a,b) gives an integer between a and b (inclusive). Useful for rolling dice: randInt(1,6).

- Run many trials: use seq(randInt(...), i, 1, N) or seq(rand( )

What's the difference between theoretical probability and simulated probability?

Theoretical probability is the probability you calculate from a known model or sample space (like 1/6 for rolling a 3 on a fair six-sided die), using rules and counting outcomes. Simulated (empirical) probability comes from running a random process many times (a simulation) and using the relative frequency of the event in those trials to estimate its probability. Simulation is explicitly in the CED (UNC-2.A): you model the random process, record counts, and use relative frequency as your estimate. By the law of large numbers, as you increase trials the simulated probability tends to get closer to the theoretical probability. On the AP exam you might be asked to set up or interpret a simulation (Skill 3.A, Topic 4.2). For practice and examples, check the Topic 4.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/estimating-probabilities-using-simulation/study-guide/ABwpnnUf4VCXeVbB9q72) and try practice questions (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

I don't understand how to model real-world situations using simulation - can you give me examples?

Think of simulation as building a fake version of a random process so you can estimate a probability by repeated trials. Short examples and how to model them: - Birthday problem (probability two students share a birthday): outcome = a class of n birthdays (1–365). Use random digits or a calculator to generate n birthdays per trial (with replacement), run 10,000 trials, record fraction with a match. (UNC-2.A, relative frequency → probability.) - Checkout wait time: use your observed distribution of service times (categorical bins or empirical CDF). For each trial, draw random service times for k customers from that distribution, compute total wait, repeat many times to estimate P(total > T). - Disease spread (simple Bernoulli model): each contact transmits with prob p. For each simulated person, run Bernoulli trials for their contacts; repeat to estimate outbreak probability. Key steps every time: define the random process/outcome, choose a way to generate random outcomes, run many trials, use relative frequency as your probability (law of large numbers). For worked examples and AP-aligned practice, see the Topic 4.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/estimating-probabilities-using-simulation/study-guide/ABwpnnUf4VCXeVbB9q72) and Unit 4 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4). For drills, try practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How many trials do I need before the law of large numbers kicks in?

Short answer: there’s no single magic number—the law of large numbers says your simulated relative frequency will tend to get closer to the true probability as you increase trials, but how many you “need” depends on how precise you want to be. Quick rule you can use on the AP: treat the simulation result p̂ like a proportion. Its standard error ≈ sqrt(p(1−p)/n). Example: if p ≈ 0.5 then SE ≈ 0.5/√n. To get SE ≈ 0.05 (about ±0.10 typical spread) you need n ≈ 100; for SE ≈ 0.01 (much tighter) you need n ≈ 2500. On AP-style simulations, 100–1,000 trials often give clear, exam-worthy estimates; use more if you need high precision. Also note CED keywords: record counts, relative frequency, and state number of trials. If you want practice setting up sims, see the Topic 4.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/estimating-probabilities-using-simulation/study-guide/ABwpnnUf4VCXeVbB9q72) and try problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

Step by step how do I estimate the probability of getting heads when flipping a coin using simulation?

1) Define the random process and event: one fair coin flip; event = “heads.” (CED: outcome, event, random process—UNC-2.A.1–3) 2) Choose a simulation method: physically flip or use random numbers (e.g., generate 0–1 where 1=head). 3) Run many trials and record outcomes: do 100, then 1,000, then 10,000 flips. For each trial count heads. (CED: simulation, trial, sample space—UNC-2.A.4) 4) Compute relative frequency: probability estimate = (number of heads) / (total trials). Example: 1,000 flips → 513 heads → estimate = 0.513. 5) Repeat/increase trials: by the law of large numbers, your estimate should get closer to true p = 0.5 as trials grow (UNC-2.A.6, UNC-2.A.5). 6) Report context and method: state how you simulated (physical, RNG, seed) and number of trials—AP exam expects clear description of simulation and use of relative frequency (Skill 3.A). For a quick refresher on AP-style simulation steps, see Fiveable’s Topic 4.2 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/estimating-probabilities-using-simulation/study-guide/ABwpnnUf4VCXeVbB9q72). For extra practice, try problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).