Once we finish organizing the set of data of our interest into a certain display of our choice, the next task is to describe the data. In other words we should tell what we see. There are three things that we should look for when trying to find trends and patterns: shape, center, and spread.

Shape

To describe the shape of the display, check the following:

- Symmetry. If you fold the histogram, do you have have equal amounts of data on each side. If yes, then your data are symmetric! Think of the shape of a butterfly and what happens when you "fold" it in half.

Symmetry in a histogram can occur if the distribution of the data is symmetric around the central value. This means that if you were to fold the histogram in half, the two halves would be approximately mirror images of each other.

A symmetric distribution is one in which the values on either side of the central value (such as the median or mean) are roughly equal. For example, a bell-shaped curve is a symmetric distribution because the values on either side of the peak are roughly equal.

To determine if a histogram is symmetric, you can visually inspect the shape of the histogram and see if it appears to be roughly symmetrical. You can also use statistical measures such as the mean and median to determine if the distribution is symmetric.

It's worth noting that a histogram does not have to be perfectly symmetrical to be considered symmetric. Some degree of skewness or asymmetry is often present in real-world data, and a histogram may still be considered symmetric if the degree of asymmetry is relatively small.

- Skewness. The shapes can be right-skew and left-skew, the least or highest number in distribution pulls it to its side, and so it makes it look skewed. The skewed distribution will have one tail longer than the other, whereas the symmetric distribution has equal tails. If the tail is longer at the left side, then it is called left skewed, and right skewed for the ones that the tail is longer on the right side

Another way to think about skewness is that there are two types of skewness: positive skewness and negative skewness. Positive skewness occurs when the distribution is skewed to the right, with a long tail on the right side and a shorter tail on the left side. This means that the majority of the values in the distribution are clustered on the left side, with a few values on the right side that are much larger or smaller.

On the other hand, negative skewness occurs when the distribution is skewed to the left, with a long tail on the left side and a shorter tail on the right side. This means that the majority of the values in the distribution are clustered on the right side, with a few values on the left side that are much smaller or larger.

Souce: ResearchGate- Peaks (modes). A mode represents the most frequent value or values in a distribution. In a histogram, stemplot, dotplot, or other graphical representation of data (except for boxplots), the mode is often indicated by the peak or peaks in the distribution.

A distribution can have one mode, in which case it is called a unimodal distribution, or it can have two or more modes, in which case it is called a multimodal distribution. A bimodal distribution, for example, is a distribution with two modes.

It's worth noting that a distribution can have a mode even if it is not symmetrical or has skewed data. For example, a positively skewed distribution (with a long tail on the right side) can still have a mode if there is a value or values that occur more frequently than any other values in the distribution.

Uniform distributions, on the other hand, do not have a mode because all of the values in the distribution occur with roughly the same frequency. In a uniform distribution, there is no single value that stands out as being more common than any other value.

Source: Towards Data ScienceIt's important to be aware of the number and location of modes in a distribution because they can provide valuable insights into the underlying data and how it is distributed. For example, the presence of two modes in a distribution may indicate the presence of two distinct groups or subpopulations within the data.

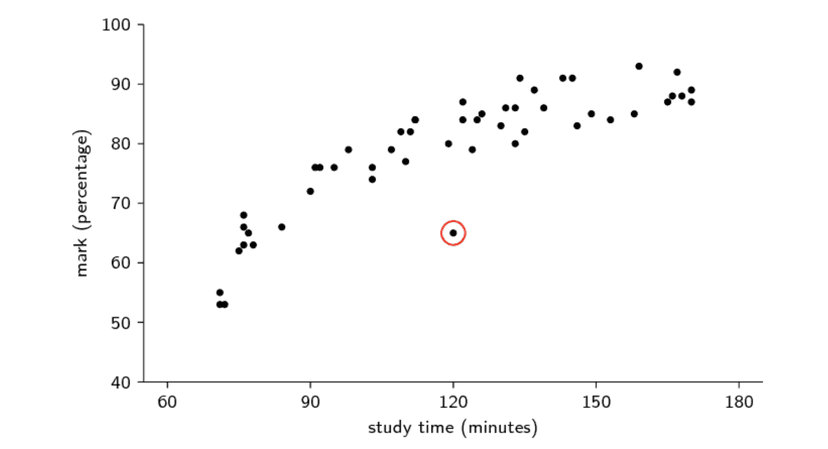

- Outlier. Beware of outliers. Outliers are values in a dataset that are significantly different from the majority of the other values in the dataset. They can be either extremely high or extremely low, and they can have a significant impact on statistical measures such as the mean, median, and range of the data.

It's important to be aware of outliers in a dataset because they can skew the results of statistical analyses and cause them to be less representative of the underlying data. For this reason, it is often useful to analyze data both with and without outliers to see how they affect the results.

There are a few different ways to identify outliers in a dataset. One way is to use graphical methods such as boxplots, which can help you visualize the distribution of the data and identify any values that are significantly different from the rest of the data. You can also use statistical measures such as the mean and standard deviation to identify outliers.

It's important to remember that outliers are not necessarily bad data, and they should not be automatically excluded from analysis. However, it is important to consider whether the outliers are representative of the underlying data or whether they may be the result of errors or other factors that need to be taken into account when interpreting the results of the analysis.

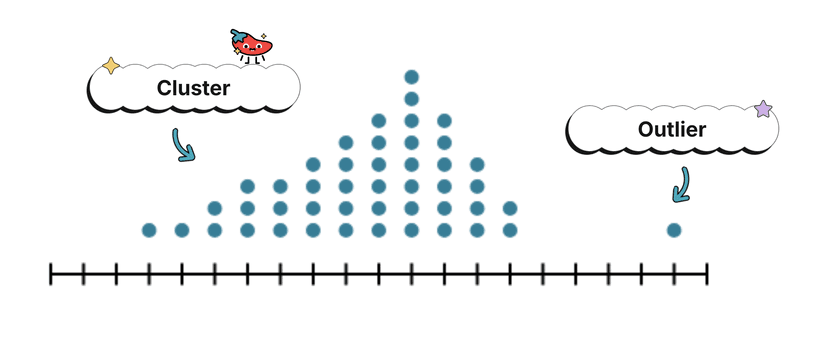

- Gaps. Gaps in data help us detect multiple modes and warn us about different groups of data sources.

Center

There are three commonly used measures of the "center" of a distribution: mean, median, and mode.

- The mean, also known as the average, is calculated by summing all of the values in a dataset and dividing by the number of values. It is often considered the best measure of central tendency for symmetric distributions because it takes into account all of the values in the dataset and reflects the overall trend in the data.

- The median is the middle value in a dataset when the values are ordered from least to greatest. It is often considered a better measure of central tendency for skewed distributions because it is resistant to the influence of outliers (values that are significantly different from the majority of the other values in the dataset).

- The mode is the value that occurs most frequently in a dataset. It is a useful measure of central tendency when there are a few values that occur much more frequently than the others.

In a symmetric distribution, the mean, median, and mode are often close to each other or even equal, depending on the exact shape of the distribution. However, in skewed distributions or datasets with outliers, the mean, median, and mode can be significantly different from each other. It's important to consider which measure of central tendency is most appropriate for a given dataset, taking into account the symmetry or skewness of the data as well as the presence of outliers.

Spread

The center is a good measure, but it's definitely not perfect if we don’t report it with the spread. There are several measures that can be used to describe the spread or dispersion of a dataset, including the range, standard deviation, and interquartile range (IQR).

- The range is calculated by subtracting the minimum value in a dataset from the maximum value. While it can be a useful measure in some cases, it has the disadvantage of not taking into account the values of all of the data points, only the maximum and minimum values. As a result, it may not accurately reflect the true variability in the data.

- The standard deviation measures the dispersion of a dataset around the mean. It is calculated by taking the square root of the variance, which is the average of the squared differences between each value in the dataset and the mean. The standard deviation is a useful measure for symmetric distributions because it takes into account all of the values in the dataset and reflects the overall pattern of the data.

- The interquartile range (IQR) is calculated by subtracting the first quartile (Q1) from the third quartile (Q3). The first quartile is the value that divides the bottom 25% of the data from the top 75%, while the third quartile is the value that divides the bottom 75% of the data from the top 25%. The IQR is often used to describe the spread of skewed distributions or datasets with outliers because it is resistant to the influence of these values.

In general, it is a good practice to report both the center and spread of a dataset when describing its statistical properties. In symmetric distributions, it is common to report the mean with the standard deviation, while in skewed distributions, it is common to report the median with the IQR. This allows you to provide a more complete description of the distribution of the data and how it is dispersed around the center.

As we go through the next couple of sections, you'll be more familiar and comfortable describing distributions in terms of shape, center, and spread... woo-hoo!

Key Vocabulary

- Shape

- Center

- Spread

- Outliers

- Symmetric

- Skewed

Vocabulary

The following words are mentioned explicitly in the College Board Course and Exam Description for this topic.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| bimodal | A distribution with two prominent peaks. |

| center | A measure indicating the middle or typical value of a distribution. |

| cluster | Concentrations of data usually separated by gaps in a distribution. |

| descriptive statistics | Methods used to summarize and describe the characteristics of a data set without making inferences about a larger population. |

| distribution | The pattern of how data values are spread or arranged across a range. |

| gap | Regions of a distribution between two data values where there are no observed data. |

| outlier | Data points that are unusually small or large relative to the rest of the data. |

| quantitative data | Data that consists of numerical values that can be measured and analyzed mathematically. |

| shape | The overall form or pattern of a distribution, including characteristics like skewness and modality. |

| skewed left | A distribution with a longer tail extending to the left, where the mean is typically less than the median. |

| skewed right | A distribution with a longer tail extending to the right, where the mean is typically greater than the median. |

| symmetric | A distribution where the left half is the mirror image of the right half. |

| uniform | A distribution where each bar height is approximately the same with no prominent peaks. |

| unimodal | A distribution with one main peak. |

| variability | The spread or dispersion of data values in a distribution. |

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I describe the shape center and spread of a data distribution?

To describe a quantitative distribution for AP Stats, cover shape, center, spread, and unusual features. Shape: say if it’s symmetric, skewed right (long right tail) or left, unimodal/bimodal, or uniform (use histogram/dotplot). Center: report median for skewed data (or mean if roughly symmetric); give a number (e.g., median ≈ 50). Spread: give IQR (with median/boxplot) and/or standard deviation (with mean); report approximate values (e.g., IQR = 20, s = 6). Unusual features: note outliers, gaps, or clusters and their values. For comparisons, state which distribution has a larger center or more variability. Use appropriate graphs (histogram, boxplot, stem-and-leaf) and language from the CED (skewness, IQR, median, mean, outlier). Practice describing real examples at Fiveable’s Topic 1.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1/describing-distribution-quantitative-variable/study-guide/4dcjgkWfLu7tmS9bDtjP) and try more problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What's the difference between skewed left and skewed right distributions?

Skewness describes which way a distribution’s tail stretches. Per the CED (UNC-1.H.3), a distribution is skewed right (positive skew) when the right tail is longer than the left—that means a few large values pull the tail to the right. In that case the mean is usually larger than the median. Skewed left (negative skew) has a longer left tail (a few unusually small values) and the mean is usually less than the median. You’ll see skewness on histograms, dotplots, and boxplots—look for the longer tail and any outliers. For AP Stats, always describe shape, center, spread, and unusual features (UNC-1.H.1) when you report skewness. Want extra practice spotting skew and comparing mean vs. median? Check the Topic 1.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1/describing-distribution-quantitative-variable/study-guide/4dcjgkWfLu7tmS9bDtjP) and Unit 1 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1). Practice problems are at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

When do I say a distribution is unimodal vs bimodal?

Say a distribution is unimodal when its graph (histogram, dotplot, stem-and-leaf) has one clear main peak—one region where observations concentrate. Call it bimodal when there are two distinct, prominent peaks (two separate concentrations) usually separated by a gap or lower-frequency region. The CED lists “one main peak = unimodal” and “two prominent peaks = bimodal” as part of describing shape (UNC-1.H.4). A couple of practical tips: small changes in histogram bin width or a noisy sample can create or hide modes, so check with different bin widths or a dotplot. Also decide whether peaks are “prominent” (meaningful clusters, not tiny bumps or outliers). If there are more than two clear peaks call it multimodal. For AP review, remember shape (including number of peaks), center, spread, and unusual features are required when you describe a quantitative distribution (see the Topic 1.6 study guide on Fiveable: https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1/describing-distribution-quantitative-variable/study-guide/4dcjgkWfLu7tmS9bDtjP). For extra practice, try problems at https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics.

I'm confused about outliers - how do I know if a data point is an outlier or not?

An outlier is a value that’s unusually small or large compared to the rest of your data (an “unusual feature” in the CED, UNC-1.H.2). The common rule AP expects you to use is the 1.5·IQR method: - Compute Q1, Q3, and IQR = Q3 − Q1. - Lower fence = Q1 − 1.5·IQR. Upper fence = Q3 + 1.5·IQR. - Any data below the lower fence or above the upper fence is an outlier. You should also eyeball graphs (boxplots, histograms, dotplots, stem-and-leaf)—an isolated point far from clusters or in a long tail looks suspicious. Always think about context: a “true” outlier might be a recording error (fix or remove) or a real extreme value you should keep. On the AP exam, name outliers as unusual features and justify them (show fences or point to the plot). For a quick review, see the Topic 1.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1/describing-distribution-quantitative-variable/study-guide/4dcjgkWfLu7tmS9bDtjP) and try practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What does it mean when a distribution is symmetric?

A symmetric distribution means the left half is basically the mirror image of the right half—counts (or heights) at equal distances from the center are about the same. In practice that means no skew (neither long right nor long left tail), and the mean and median are very close (often equal). You’ll see symmetry on histograms, dotplots, or stem-and-leaf plots and in a roughly symmetric boxplot (whiskers about equal). The normal curve is the classic symmetric, unimodal example. On the AP exam you’ll be expected to describe shape (symmetric vs. skewed), center, and spread as part of UNC-1.H / Skill 2.A, so note symmetry when comparing distributions. For a refresher, check the Topic 1.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1/describing-distribution-quantitative-variable/study-guide/4dcjgkWfLu7tmS9bDtjP) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I identify gaps and clusters in a histogram?

Look across the bars and ask: where are there runs of bars with little or no height (gaps) and where are there groups of tall bars close together (clusters)? Per the CED, a gap is a region with no observed data and clusters are concentrations of data separated by gaps (UNC-1.H.5–6). Quick checklist: - Scan for empty bins: any contiguous x-interval with no bars (or zero/very small counts) is a gap. Give its approximate x-range. - Find concentrations: one or more adjacent bins with noticeably higher counts = a cluster. Report the x-range and roughly how many observations or percent fall there. - Note modality: clusters often show up as separate peaks (bimodal/multimodal). - Be careful: bin width/placement can create or hide gaps/clusters—confirm with a dotplot or stem-and-leaf if possible. - Always describe in context (units, variable) and mention if a gap suggests distinct subgroups or data collection issues. For AP review, see the Topic 1.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1/describing-distribution-quantitative-variable/study-guide/4dcjgkWfLu7tmS9bDtjP) and practice related problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

Can someone explain step by step how to describe a quantitative distribution?

Start with a graph (histogram, dotplot, stem-and-leaf or boxplot). Then describe these five parts in this order—shape, center, spread, unusual features, and context (this matches the CED UNC-1.H): 1. Shape: modal (unimodal/bimodal), symmetry or skew (right = long right tail, left = long left tail). 2. Center: give median for skewed data or mean for roughly symmetric; state the value (e.g., median ≈ 50). 3. Spread: give range and IQR (or standard deviation if using the mean); report numbers (e.g., IQR = 20, range = 0–200). 4. Unusual features: point out outliers, gaps, clusters, or multiple peaks and where they lie. Use the 1.5·IQR rule for outliers if needed. 5. Context & comparison: tie everything to the real units and the question you’re answering. On the AP exam, be concise and use these keywords (skewness, unimodal/bimodal, outlier, IQR, mean/median). For a quick review, see the Topic 1.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1/describing-distribution-quantitative-variable/study-guide/4dcjgkWfLu7tmS9bDtjP) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What's the formula for finding outliers in a dataset?

Use the IQR (boxplot) rule. Find Q1 (25th percentile) and Q3 (75th percentile), then IQR = Q3 − Q1. - Lower fence = Q1 − 1.5×IQR - Upper fence = Q3 + 1.5×IQR Any data point below the lower fence or above the upper fence is an outlier for one-variable data (UNC-1.H.2). Some people call points beyond Q1 − 3×IQR or Q3 + 3×IQR “extreme” outliers. This rule is what you’ll use when describing unusual features with boxplots on the AP exam's exploring-one-variable tasks (Topic 1.6). For a quick review, see the Topic 1.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1/describing-distribution-quantitative-variable/study-guide/4dcjgkWfLu7tmS9bDtjP) and try practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

I don't understand the difference between positive skew and negative skew - which way do the tails go?

Think of the tail as the long thin end of the distribution that sticks out away from the bulk of the data. - Positive skew (skewed to the right): the right tail is longer—most data are on the left (lower values) and a few large values pull the tail to the right. Mean > median is common. - Negative skew (skewed to the left): the left tail is longer—most data are on the right (higher values) and a few small values pull the tail to the left. Mean < median is common. - Symmetric: left and right sides mirror each other (mean ≈ median). On the AP, use this language when describing shape (UNC-1.H.3) in histograms, dotplots, or boxplots. For a quick refresher, see the Topic 1.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1/describing-distribution-quantitative-variable/study-guide/4dcjgkWfLu7tmS9bDtjP) and practice lots of graphs at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I know if a distribution is approximately uniform?

A distribution is approximately uniform when the graph (usually a histogram, dotplot, or stem-and-leaf) shows no clear peaks and the heights (or counts) across bins are roughly the same—i.e., the data are spread evenly across the range. On the AP CED this is UNC-1.H.4: “each bar height is approximately the same (no prominent peaks).” How to check in practice: look at a histogram with sensible bin widths—if most bins have similar frequencies (allowing for sampling noise), no long tails, no gaps or clusters, call it approx uniform. Don’t confuse small random ups and downs with real peaks; with small samples bin choice matters. Use other graphs (dotplot, stem plot) to confirm even spacing. For AP tasks, describe shape, center, and variability and note any unusual features (UNC-1.H.1). Want a quick review and practice? See the Topic 1.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1/describing-distribution-quantitative-variable/study-guide/4dcjgkWfLu7tmS9bDtjP) and try practice problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

When describing a distribution what order should I talk about shape center and variability?

Do shape first, then center, then variability—and always finish by noting any unusual features. That order matches the AP CED: UNC-1.H lists shape, center, and spread as the core descriptors. So say something like: (1) Shape—unimodal/bimodal, symmetric or skewed (right/left), any gaps or clusters; (2) Center—give median for skewed data (or mean if roughly symmetric) and state the value; (3) Variability—give range and IQR for skewed data (or standard deviation for symmetric), plus the numeric values; (4) Unusual features—call out outliers, gaps, clusters, or multiple peaks in context. On the exam, be concise and include numbers (medians/means, IQR/SD, ranges) and context (what the variable is). Want more examples and practice? Check the Topic 1.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1/describing-distribution-quantitative-variable/study-guide/4dcjgkWfLu7tmS9bDtjP) and try problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What are unusual features I need to look for when analyzing data distributions?

When you describe a quantitative distribution, always look for unusual features beyond shape/center/spread. Key things to spot (CED UNC-1.H): - Outliers—values unusually small/large. Identify with a boxplot or the 1.5·IQR rule; they can pull the mean away from the median. - Gaps—ranges with no observations; suggest breakpoints or different subgroups. - Clusters—concentrations of data separated by gaps; report number/location of clusters. - Multiple peaks (modes)—unimodal, bimodal, or multimodal; multiple peaks can mean mixed populations. - Skewness—right (long right tail) or left (long left tail); mention how skew affects mean vs median. On the AP exam, you should describe these in context and use graphs (histogram/boxplot/dotplot) to justify claims (Unit 1, Topic 1.6). For a quick review, see the Topic 1.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1/describing-distribution-quantitative-variable/study-guide/4dcjgkWfLu7tmS9bDtjP) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I describe multiple peaks in a distribution?

When you see more than one peak, call out that unusual feature right away and use AP terms: bimodal (two peaks) or multimodal (more than two). Describe each peak’s location (approximate x-values), relative height (which peak is taller), and whether peaks form clusters separated by gaps. Then finish your distribution description with shape, center, and spread—e.g., “bimodal, peaks near 30 and 70, taller peak at 30; overall right-skewed; median ≈ 45; range ≈ 80.” Mention any gaps or outliers between peaks. On the AP exam, UNC-1.H expects you to note multiple peaks as an “unusual feature” along with center and variability. For quick review, see the Topic 1.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1/describing-distribution-quantitative-variable/study-guide/4dcjgkWfLu7tmS9bDtjP) and try practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics) to get fluent at phrasing these descriptions.

I keep mixing up left skewed and right skewed - is there a trick to remember which is which?

Think of the tail as the part that’s stretched out—the distribution is named for the side the tail points to. If the long tail is on the right (higher values), it’s right-skewed (positive skew); if the long tail is on the left (lower values), it’s left-skewed (negative skew). Quick checks you can use: (1) tail direction trick—tail points to “right” or “left”; (2) mean vs. median—mean is pulled toward the tail (for right skew mean > median; for left skew mean < median). On the AP CED this is UNC-1.H (shape and skewness) and appears on one-variable data questions, so be ready to say which tail is longer and how center measures compare. For more practice and examples, see the Topic 1.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1/describing-distribution-quantitative-variable/study-guide/4dcjgkWfLu7tmS9bDtjP) and tons of practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What's the difference between describing data vs making inferences about a population?

Describing data = summarizing the sample you actually have. You use graphs (histogram, boxplot, dotplot, stem-and-leaf) and descriptive stats (shape, center = mean/median, spread = IQR/SD, outliers, gaps, clusters, modality) to report what those observations look like. Descriptive stats do NOT claim anything about a larger group—they just describe the dataset (CED: UNC-1.H, UNC-1.H.1–H.6, UNC-1.H.7). Making inferences = using sample data PLUS probability ideas to draw conclusions about a population. That’s confidence intervals and hypothesis tests based on sampling distributions, standard errors, and conditions (random sample/randomization, independence, and appropriate sample size/normality). Inference accounts for sampling variability and gives uncertainty (p-values, margins of error) about population parameters. If you want guided practice on describing distributions, check the Topic 1.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-1/describing-distribution-quantitative-variable/study-guide/4dcjgkWfLu7tmS9bDtjP) and try extra problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).