It's very useful to transform a random variable by adding or subtracting a constant or multiplying or dividing by a constant. This can help to simplify calculations or to make the results easier to interpret.

This section is about transforming random variables by adding/subtracting or multiplying/dividing by a constant. At the end of this section, you'll know how to combine random variables to calculate and interpret the mean and standard deviation.

Linear Transformations of a Random Variable

When you transform a random variable by adding or subtracting a constant, the mean and standard deviation of the transformed variable are also shifted by the same constant. For example, if you have a random variable, X, with mean E(X) and standard deviation SD(X), and you transform it to a new random variable, Y, by adding a constant, c, to each value of X, then the mean and standard deviation of Y are given by: + & -

E(Y) = E(X) + c

SD(Y) = SD(X)

Similarly, if you transform a random variable by multiplying or dividing it by a constant, the mean and standard deviation of the transformed variable are also multiplied or divided by the same constant. For example, if you have a random variable, X, with mean E(X) and standard deviation SD(X), and you transform it to a new random variable, Y, by multiplying each value of X by a constant, c, then the mean and standard deviation of Y are given by: × & ÷

E(Y) = E(X) * c

SD(Y) = SD(X) * c

Y = a + BX

When you transform a random variable by adding or subtracting a constant, it affects the measures of center and location, but it does not affect the variability or the shape of the distribution.

When you transform a random variable by multiplying or dividing it by a constant, it affects the measures of center, location, and variability, but it does not change the shape of the distribution.

Expected Value of the Sum/Difference of Two Random Variables

It is also possible to combine two or more random variables to create a new random variable. To calculate the mean and standard deviation of the combined random variable, you would need to use the formulas for the expected value and standard deviation of a linear combination of random variables.

For example, if you have two random variables, X and Y, with means E(X) and E(Y) and standard deviations SD(X) and SD(Y), respectively, and you want to create a new random variable, Z, by adding them together, then the mean of Z is given by:

E(Z) = E(X) + E(Y)

Summary

Sum: For any two random variables X and Y, if S = X + Y, the mean of S is mean S = mean X + mean Y. Put simply, the mean of the sum of two random variables is equal to the sum of their means.

Difference: For any two random variables X and Y, if D = X - Y, the mean of D is meanD = meanX - meanY. The mean of the difference of two random variables is equal to the difference of their means. The order of subtraction is important.

Independent Random Variables: If knowing the value of X does not help us predict the value of X, then X and Y are independent random variables.

Standard Deviation of the Sum/Difference of Two Random Variables

For example, if you have two random variables, X and Y, with means E(X) and E(Y) and standard deviations SD(X) and SD(Y), respectively, and you want to create a new random variable, Z, by adding them together, then the standard deviation of Z is given by:

SD(Z) = √(SD(X)^2 + SD(Y)^2)

Summary

Sum: For any two independent random variables X and Y, if S = X + Y, the variance of S is SD^2= (X+Y)^2 . To find the standard deviation, take the square root of the variance formula: SD = sqrt(SDX^2 + SDY^2). Standard deviations do not add; use the formula or your calculator.

Difference: For any two independent random variables X and Y, if D = X - Y, the variance of D is D^2= (X-Y)^2=x2+Y2. To find the standard deviation, take the square root of the variance formula: D=sqrt(x2+Y2). Notice that you are NOT subtracting the variances (or the standard deviation in the latter formula).

🎥 Watch: AP Stats - Combining Random Variables

Practice Problem

Try this one on your own!

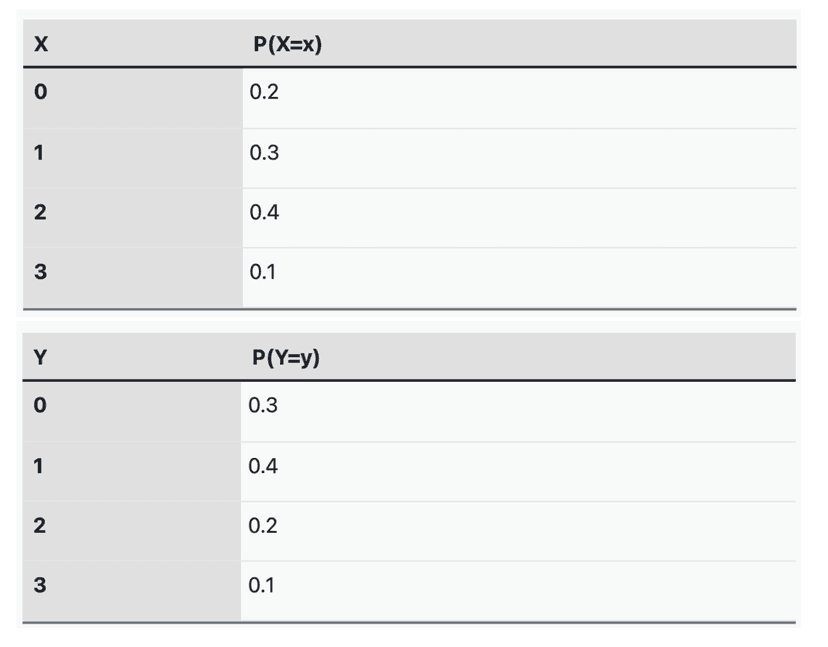

Two random variables, X and Y, represent the number of hours a student spends studying for a math test and the number of hours a student spends studying for a science test, respectively. The probability distributions of X and Y are shown in the tables below:

A new random variable, Z, represents the total number of hours a student spends studying for both tests.

(a) Calculate the mean or expected value of Z.

(b) Calculate the standard deviation of Z.

(d) Interpret the results in the context of the problem.

Vocabulary

The following words are mentioned explicitly in the College Board Course and Exam Description for this topic.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| independent random variables | Random variables where knowing the value or probability distribution of one does not change the probability distribution of the other. |

| linear combinations | Expressions of the form aX + bY where X and Y are random variables and a and b are real number coefficients. |

| linear transformations | Changes to a random variable of the form Y = a + bX, where a and b are constants that shift and scale the distribution. |

| mean | The average value of a dataset, represented by μ in the context of a population. |

| probability distribution | A function that describes the likelihood of all possible values of a random variable. |

| random variable | A variable whose value is determined by the outcome of a random phenomenon and can take on different numerical values with associated probabilities. |

| standard deviation | A measure of how spread out data values are from the mean, represented by σ in the context of a population. |

| variance | A measure of the spread or dispersion of a probability distribution, denoted as σ², indicating how far values typically deviate from the mean. |

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I find the mean when I'm adding two random variables together?

If X and Y are random variables and you form a linear combination aX + bY, the mean is just the same linear combo of the means: E(aX + bY) = a·μX + b·μY. This is the linearity of expectation (VAR-5.E.1). Important: you do NOT need X and Y to be independent to use this for the mean—independence matters for variance, not the mean. Example: if X has mean 3 and Y has mean 5, then E(X+Y)=3+5=8; E(2X−Y)=2·3−1·5=1. On the AP exam you may be asked to compute parameters of sums/differences (VAR-5.E, VAR-5.F), so remember: means add linearly; variances add as a²σ²X + b²σ²Y only when X and Y are independent (VAR-5.E.3). For a quick review see the Topic 4.9 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/combining-random-variables/study-guide/4a4RK1Yx83jckDNdzaX6) and more unit resources (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4). Practice these on Fiveable’s practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What's the formula for the variance of aX + bY?

If X and Y are any random variables, the variance of a linear combination is Var(aX + bY) = a^2 Var(X) + b^2 Var(Y) + 2ab Cov(X,Y). If X and Y are independent (the CED emphasizes this), Cov(X,Y)=0, so the AP-friendly formula is Var(aX + bY) = a^2 σ_X^2 + b^2 σ_Y^2. Example: if a = 2 and b = 3 and X and Y are independent, Var(2X+3Y) = 4σ_X^2 + 9σ_Y^2. Remember: linearity of expectation always holds for means (E[aX+bY]=aμ_X+bμ_Y) but the variance sum rule a^2σ_X^2 + b^2σ_Y^2 requires independence (VAR-5.E in the CED). For a single linear transform Y = a + bX, σ_Y = |b| σ_X (VAR-5.F). For more review, see the Topic 4.9 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/combining-random-variables/study-guide/4a4RK1Yx83jckDNdzaX6) and try practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

When do I use the independence formula vs the regular formula for combining random variables?

Use the independence formula when X and Y are independent; otherwise use the general formula that includes covariance. - Means: always use linearity of expectation. E(aX + bY) = aμX + bμY whether or not X and Y are independent (VAR-5.E.1). - Variances: if X and Y are independent, Var(aX + bY) = a^2σX^2 + b^2σY^2 (VAR-5.E.3). If they are not independent, use the full rule: Var(aX + bY) = a^2σX^2 + b^2σY^2 + 2ab·Cov(X,Y). Cov(X,Y) = 0 when X and Y are independent, which is why the independence formula drops the covariance term. On the AP exam you should always state your independence assumption before applying the simpler variance rule (CED Topic 4.9). Want a quick refresher + examples? Check the Topic 4.9 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/combining-random-variables/study-guide/4a4RK1Yx83jckDNdzaX6) and practice problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

I'm confused about linear transformations - what happens to the mean and standard deviation when Y = a + bX?

If Y = a + bX, the mean and spread change in simple, predictable ways: - Mean: μY = a + b·μX. Adding a shifts the center by a; multiplying by b scales the center by b. - Standard deviation: σY = |b|·σX. Adding a doesn’t change spread; multiplying by X by b stretches/compresses variability by |b| (use absolute value because SD is always nonnegative). - Shape: the distribution’s shape is preserved (just shifted/scaled); note the CED says shape preserved when a>0 and b>0, but more generally multiplying by a negative b also flips the distribution left–right while keeping spread |b| times original. This is exactly VAR-5.F in the CED (linearity of expectation, scaling of SD). You’ll see these on Topic 4.9 items on the exam—practice applying them with problems in the Topic 4.9 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/combining-random-variables/study-guide/4a4RK1Yx83jckDNdzaX6) and more practice at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I know if two random variables are independent?

Two random variables are independent when knowing the value (or outcome) of one gives you no information about the other. In AP terms: the probability distribution of one does not change when you condition on the other (CED VAR-5.E.2). How to check: - Discrete case: P(X = x and Y = y) = P(X = x)·P(Y = y) for every pair (x,y). If that holds, X and Y are independent. - Continuous case: the joint density factors: fX,Y(x,y) = fX(x)·fY(y) for all x,y. - Shortcut/filters: if you’re told X and Y are independent, you may use Var(aX + bY) = a^2σX^2 + b^2σY^2 (CED VAR-5.E.3). But note: Cov(X,Y)=0 (or uncorrelated) does NOT always imply independence except in special cases (e.g., jointly normal). On the AP exam they’ll usually state independence or give joint probabilities/densities so you can test the factorization. For a quick refresher, see the Topic 4.9 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/combining-random-variables/study-guide/4a4RK1Yx83jckDNdzaX6) and try practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

Can someone explain step by step how to calculate the parameters when combining random variables?

Step-by-step: start with the form of the combination and the CED rules. 1) Write the linear combo: T = aX + bY (or T = a + bX for a transform). 2) Mean (always): μT = a·μX + b·μY. If T = c + dX, then μT = c + d·μX. (CED VAR-5.E.1, VAR-5.F.1) 3) Check independence: variance rule below requires X and Y independent (CED VAR-5.E.2). 4) Variance (if independent): Var(T) = a^2·σX^2 + b^2·σY^2. If T = c + dX, Var(T) = d^2·σX^2 and σT = |d|·σX (CED VAR-5.E.3, VAR-5.F.1). 5) Standard deviation: σT = sqrt(Var(T)). 6) Interpret: give units and context (means add linearly; variances add after squaring coefficients). Example: If T = 2X − Y, μX=5, μY=3, σX=4, σY=2 and independent: μT = 2·5 − 1·3 = 7; Var(T)=4·16 + 1·4 = 68; σT=√68 ≈ 8.25. For AP review see the Topic 4.9 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/combining-random-variables/study-guide/4a4RK1Yx83jckDNdzaX6). For more practice, Fiveable has tons of practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What's the difference between dependent and independent random variables in terms of variance?

If X and Y are independent, their covariance is 0, so variances add (with coefficients): for real a,b, Var(aX + bY) = a^2 Var(X) + b^2 Var(Y). This is the AP formula in VAR-5.E.3. If X and Y are dependent, you must include covariance: Var(aX + bY) = a^2 Var(X) + b^2 Var(Y) + 2ab·Cov(X,Y). Cov(X,Y) can be positive or negative, so dependence can increase the combined variance (positive covariance) or decrease it (negative covariance). A special case: Var(a + bX) = b^2 Var(X) (VAR-5.F.1)—adding a constant a doesn’t change variance. For AP exam practice, be ready to identify independence (so Cov = 0) and use the full formula when variables are dependent. Review Topic 4.9 on Fiveable (study guide: https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/combining-random-variables/study-guide/4a4RK1Yx83jckDNdzaX6) and try practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

I don't understand why the variance formula has a squared and b squared - why do we square the coefficients?

Variance measures average squared deviation from the mean, so when you scale a random variable by a constant, you scale its deviations by that constant and the squares of those deviations by the constant squared. Concretely, if Y = aX then Var(Y) = E[(aX − aE[X])^2] = a^2E[(X − E[X])^2] = a^2Var(X). For a linear combination aX + bY (and X, Y independent), the cross-term drops (no covariance), so Var(aX + bY) = a^2Var(X) + b^2Var(Y). That’s why the coefficients are squared in the VAR-5.E.3 formula from the CED. Note: means are linear so E(aX + bY) = aE[X] + bE[Y] (no squaring). Also remember standard deviation scales by |a| (σY = |a|σX), which matches Var scaling by a^2. If you want more practice or AP-style examples, check the Topic 4.9 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/combining-random-variables/study-guide/4a4RK1Yx83jckDNdzaX6) and more practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I solve problems where I have to find the mean and variance of something like 3X + 2Y?

Use linearity of expectation first: E(3X+2Y) = 3E(X) + 2E(Y). For variance, if X and Y are independent (CED VAR-5.E.3), Var(3X+2Y) = 3^2Var(X) + 2^2Var(Y) = 9Var(X) + 4Var(Y). The standard deviation of the sum is the square root of that. If X and Y are NOT independent, include covariance: Var(3X+2Y) = 9Var(X) + 4Var(Y) + 2·3·2·Cov(X,Y) = 9Var(X)+4Var(Y)+12Cov(X,Y). Quick numeric example: let μX=10, σX=2 (VarX=4); μY=3, σY=4 (VarY=16). Then E(3X+2Y)=3·10+2·3=36; Var(3X+2Y)=9·4+4·16=36+64=100 so SD = 10. Remember AP exam expects you to state independence when you use the simple sum-of-variances rule (VAR-5.E). For a refresher and practice problems, see the Topic 4.9 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/combining-random-variables/study-guide/4a4RK1Yx83jckDNdzaX6) and the Unit 4 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4).

When I transform a random variable with Y = a + bX, does the shape of the distribution change?

Short answer: No—a linear transformation Y = a + bX does not change the shape of X’s distribution; it just shifts and/or rescales it. Why: adding a (the +a) shifts the distribution left/right (changes center: μY = a + bμX) but doesn’t change shape or spread. multiplying by b rescales spread: σY = |b|σX. If b>0 the distribution keeps the same orientation (same shape); if b<0 you also get a reflection (shape preserved but flipped left↔right). These are the VAR-5.F and VAR-5.E ideas on the CED: linear transformations preserve shape and change mean and standard deviation in predictable ways. Use |b| for SD and sign(b) to check reflection. If you want a quick review, check the Topic 4.9 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/combining-random-variables/study-guide/4a4RK1Yx83jckDNdzaX6). For extra practice, try problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What happens to the standard deviation when I multiply a random variable by a negative number?

If you multiply a random variable X by a negative number b, the standard deviation is multiplied by |b|—it becomes |b|·σX. That means the size of spread scales by the absolute value of the multiplier, so a factor of −2 doubles the standard deviation (2·σX) even though the distribution is reflected left–right. Variance uses b^2, so sign is lost there (Var(bX) = b^2·Var(X)). The mean does change sign when b is negative (E(bX) = b·μX), and the distribution’s shape is preserved but flipped when b<0. This is exactly in the CED (VAR-5.F.1 and VAR-5.E.3) and is tested under Topic 4.9 combining random variables. For a quick recap, check Fiveable’s Topic 4.9 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/combining-random-variables/study-guide/4a4RK1Yx83jckDNdzaX6) and use extra practice problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

I missed class - what are the key formulas I need to memorize for combining random variables?

Here are the short, AP-tested formulas you should memorize for combining random variables (Topic 4.9 / VAR-5): - Linearity of expectation (always true): E(aX + bY) = a·μX + b·μY (so E(X±Y)=μX ± μY) - Variance of a linear combination (general): Var(aX + bY) = a²·Var(X) + b²·Var(Y) + 2ab·Cov(X,Y) - Variance when X and Y are independent (Cov = 0): Var(aX + bY) = a²·σX² + b²·σY² (so Var(X±Y) = Var(X) + Var(Y) for independent RVs) - Linear transformation of one variable (VAR-5.F): If Y = a + bX, then μY = a + b·μX and σY = |b|·σX. The CED notes the transformed distribution keeps the same shape so long as a>0 and b>0. Exam notes: independence is required to drop the covariance term. The formula sheet is provided on the AP exam, but you should still memorize these (they’re used a lot). For a focused study guide, check this Fiveable page (Topic 4.9) (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/combining-random-variables/study-guide/4a4RK1Yx83jckDNdzaX6). For more practice problems, go to (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I tell from a word problem whether the random variables are independent or not?

Independence means knowing one variable’s outcome doesn’t change the probability distribution of the other (CED VAR-5.E.2). In word problems look for explicit clues: - Independent: separate, unrelated trials (different people/things selected at random with replacement or from a very large population so one choice doesn’t affect another). Often the problem will say “independent,” “randomly selected,” or you can use the 10% condition (sample ≤10% of population) to treat selections as independent for the exam. - Dependent: outcomes tied by a constraint or shared source (e.g., “2 students chosen from the same class,” “given that,” totals fixed like drawing without replacement from a small deck, or when one variable is defined using the other). If probabilities change after one event, they’re dependent. Why it matters for Topic 4.9: you can always add means (VAR-5.E.1), but you may only add variances using σ²_X+σ²_Y when X and Y are independent (VAR-5.E.3). On the AP exam, explicitly state independence before using the variance-sum rule. For more examples and practice, see the Combining Random Variables study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/combining-random-variables/study-guide/4a4RK1Yx83jckDNdzaX6) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

Why does knowing information about one variable affect the other when they're dependent?

When X and Y are dependent, information about one changes the probabilities for the other because their outcomes are linked—knowing X changes the conditional distribution of Y. The CED definition of independence says: “Two random variables are independent if knowing information about one does not change the probability distribution of the other.” So for dependent variables, P(Y | X = x) ≠ P(Y). That change is often measured by covariance or conditional probabilities: if Cov(X,Y) ≠ 0 (or P(Y|X) differs across x), X and Y are dependent. Think of a concrete example: X = weather (rainy/sunny), Y = number of umbrellas sold. Learning it’s rainy (X) raises the chance that umbrella sales (Y) are high. That changed distribution is exactly what “dependent” means. For linear combinations, dependence matters because Var(aX + bY) = a²Var(X) + b²Var(Y) + 2ab·Cov(X,Y); the extra 2ab·Cov term disappears only when X and Y are independent (Cov = 0). For a short review, see the Topic 4.9 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/combining-random-variables/study-guide/4a4RK1Yx83jckDNdzaX6) and try practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

Can you walk me through a complete example of finding mean and variance for a linear combination?

Take X with μX = 10, σX^2 = 4 and Y with μY = 6, σY^2 = 9, and assume X and Y are independent (important for the variance rule). Find parameters for Z = 3X − 2Y + 5. Step 1—Mean (linearity of expectation, VAR-5.E): μZ = 3μX − 2μY + 5 = 3(10) − 2(6) + 5 = 30 − 12 + 5 = 23. Step 2—Variance (independence needed, VAR-5.E.3): Constants don’t affect variance, and coefficients square: Var(Z) = 3^2 Var(X) + (−2)^2 Var(Y) = 9(4) + 4(9) = 36 + 36 = 72. So σZ = sqrt(72) = 6√2 ≈ 8.49. Interpretation: the linear shift (+5) moves the center to 23 but doesn’t change spread; scaling by 3 and −2 increases variance by factors 9 and 4. For more practice and CED-aligned review on combining random variables, see the Fiveable study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-4/combining-random-variables/study-guide/4a4RK1Yx83jckDNdzaX6) and lots of practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).