Selecting the proper experimental design depends on the situation presented and the experimental units given. You need to be able to identify when it is appropriate to utilize a certain type of experiment. Make sure you understand the differences between the types of experiments and how to create the treatment groups randomly and you'll be a master of experimental design in no time!

Essential Knowledge

While completely randomized designs are the simplest statistical designs for experiments, there are times when the simplest method for yielding precise results is not completely randomized. There are three main designs that you can use after selecting a sample for your experiment. Don't mix up the language of experiments and the language of sample surveys!

The Big Three

- Completely Randomized Design - Experimental units are randomly assigned to treatments equally by chance.

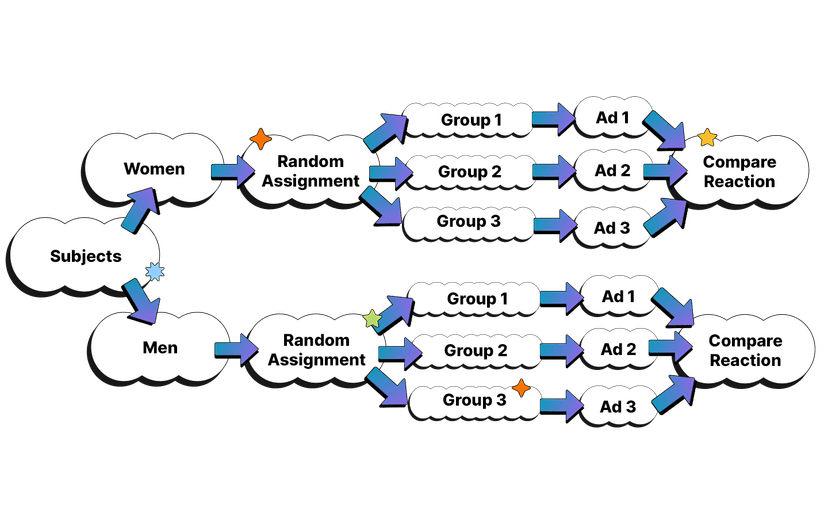

- Blocking Design - Sort groups of individuals that are known to be similar in some way that can expect different results. Do not randomize those groups together. USE ALL BLOCKS in a blocked experiment.

- Matched Pairs Design - A common type of block for comparing two treatments with similar individuals or identical treatment methods.

Longer explanations below:

In a completely randomized design, experimental units are randomly assigned to treatments equally by chance. This means that each unit has an equal probability of being assigned to any of the treatment groups, and the treatment groups are similar in terms of known confounding variables. A completely randomized design is useful for studying the effects of one or more treatments on a response variable, without considering the influence of other variables.

In a blocking design, experimental units are sorted into groups (called blocks) based on a variable that is known to influence the response variable. The units within each block are expected to be similar to each other with respect to this variable. The treatments are then randomly assigned to the units within each block. By using a blocking design, researchers can control for variables that may influence the response variable and reduce the potential for bias.

A matched pairs design is a special case of a blocking design in which experimental units are arranged in pairs that are matched on relevant factors, such as age, gender, or other characteristics. The pairs are then given both treatments, either by randomly assigning one treatment to one member of the pair and the other treatment to the second member of the pair, or by giving each subject both treatments. A matched pairs design is useful for comparing the effects of two treatments on a response variable, while controlling for known confounding variables.

Practice Problems

(1) A researcher is interested in studying the effectiveness of a new teaching method for high school math students. The researcher plans to randomly assign 50 students to either the control group or the experimental group. The control group will receive the traditional teaching method, while the experimental group will receive the new teaching method.

At the end of the study, the researcher will administer a math achievement test to all of the students. The researcher will then compare the mean math achievement scores of the two groups to determine if the new teaching method is more effective than the traditional method.

The researcher wants to use a completely randomized design for this study.

Write a detailed plan for how the researcher should set up the completely randomized design, including how the students should be assigned to the control and experimental groups.

(2) A researcher is interested in studying the effectiveness of a new study technique on college students' grades. The researcher plans to recruit 100 students from a large university and randomly assign them to either the control group or the experimental group. The control group will receive the traditional study technique, while the experimental group will receive the new study technique.

However, the researcher is aware that students' grades can be affected by their major and the difficulty of their course load. To control for these factors, the researcher wants to use a blocking design in the study.

Write a detailed plan for how the researcher should set up the blocking design, including how the students should be assigned to the control and experimental groups and how the researcher should control for major and course load.

(3) A researcher is interested in studying the effectiveness of a new study technique on college students' grades. The researcher plans to recruit 100 students from a large university and randomly assign them to either the control group or the experimental group. The control group will receive the traditional study technique, while the experimental group will receive the new study technique.

The researcher is considering using a completely randomized design, a blocking design, or a matched pairs design for the study.

Write a detailed explanation of the advantages and disadvantages of each design and recommend which design the researcher should use, providing a rationale for your recommendation.

Answers

(1) To set up the completely randomized design for this study, the researcher should first compile a list of all 50 students who will participate in the study. The researcher should then randomly assign each student to either the control group or the experimental group using a random number generator or a computer program that generates random assignments.

Once the students have been randomly assigned to the two groups, the researcher should begin implementing the two different teaching methods. The control group should receive the traditional teaching method, while the experimental group should receive the new teaching method.

After the study has been completed, the researcher should administer the math achievement test to all of the students. The researcher should then calculate the mean math achievement scores for both the control and experimental groups.

To determine if the new teaching method is more effective than the traditional method, the researcher should compare the mean math achievement scores of the two groups. If the mean score for the experimental group is significantly higher than the mean score for the control group, the researcher can conclude that the new teaching method is more effective.

or (in bullet form)

- Compile a list of all 50 students who will participate in the study

- Randomly assign each student to either the control group or the experimental group using a random number generator or a computer program that generates random assignments

- Implement the two different teaching methods: traditional method for the control group, new method for the experimental group

- Administer a math achievement test to all of the students

- Calculate the mean math achievement scores for both the control and experimental groups

- Compare the mean scores to determine if the new teaching method is more effective than the traditional method

(2)

To set up the blocking design, the researcher should first gather information on each student's major and course load. The researcher could do this by collecting data on the students' transcripts or by administering a survey to the students.

Next, the researcher should divide the students into groups based on their major and course load. For example, the researcher could create blocks for students with similar majors (e.g. biology, psychology, engineering) and blocks for students with similar course loads (e.g. heavy, moderate, light).

Within each block, the researcher should randomly assign students to either the control group or the experimental group using a random number generator or a computer program that generates random assignments. This will ensure that the two groups are balanced within each block in terms of major and course load.

Once the students have been randomly assigned to the two groups within each block, the researcher should begin implementing the two different study techniques. The control group should receive the traditional study technique, while the experimental group should receive the new study technique.

At the end of the study, the researcher should collect data on the students' grades and compare the mean grades of the two groups to determine if the new study technique is more effective than the traditional technique.

or (in bullet form)

- Gather information on each student's major and course load

- Divide the students into groups based on their major and course load (e.g. biology major, heavy course load; psychology major, moderate course load)

- Within each block, randomly assign students to either the control group or the experimental group using a random number generator or a computer program that generates random assignments

- Implement the two different study techniques: traditional technique for the control group, new technique for the experimental group

- Collect data on the students' grades and compare the mean grades of the two groups to determine if the new study technique is more effective than the traditional technique

(3)

- A completely randomized design involves randomly assigning the participants to the two groups without considering any other factors. The advantage of this design is that it is simple and easy to implement. However, it is not always the best choice because it does not control for any extraneous variables that could affect the outcome of the study.

- A blocking design involves dividing the participants into groups based on a particular factor (called a "blocking variable") and then randomly assigning participants within each group to the two treatment conditions. This design is useful when there are variables that the researcher wants to control for but cannot manipulate. The advantage of this design is that it can help reduce the influence of extraneous variables on the outcome of the study. However, it requires more advanced planning and may not always be feasible depending on the available resources and the number of participants.

- A matched pairs design involves pairing participants based on a particular factor (such as age, gender, or ability level) and then randomly assigning one member of each pair to the control group and the other member to the experimental group. This design is useful when the researcher wants to control for a specific variable and has a small number of participants. The advantage of this design is that it can reduce the influence of extraneous variables on the outcome of the study. However, it can be time-consuming and may not always be feasible depending on the available resources and the number of participants.

In this case, the researcher should consider using a blocking design. The blocking design would allow the researcher to control for factors such as major and course load that could affect the students' grades. Additionally, the blocking design would be more practical than the matched pairs design, as it would not require pairing students and would be more feasible with a larger number of participants. However, the researcher should carefully consider the resources and time available before deciding which design to use.

Vocabulary

The following words are mentioned explicitly in the College Board Course and Exam Description for this topic.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| experimental design | A structured plan for conducting an experiment that specifies how treatments will be assigned to experimental units and how data will be collected. |

| experimental unit | The participants or subjects to which treatments are assigned in an experiment. |

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I know which experimental design to pick for my AP Stats project?

Pick the design that best answers your research question while controlling variation and practical limits. Ask: is my goal to compare treatments (causal) or just observe? If causal, use a randomized controlled trial (randomize treatments to experimental units) to reduce confounding. If a known blocking variable (age, gender, baseline score) affects response, use a randomized block design to reduce variability. For paired or before–after comparisons, use matched pairs or a crossover (each unit gets both treatments at different times)—remember possible carryover effects. Use a completely randomized design when units are similar and resources are limited. Always plan replication (enough units), randomization, and blinding (single/double) if possible to reduce bias and confounding. Explain your choice in AP terms: name the design, justify why it controls variation and fits resources (VAR-3.D.1), and note limitations. For quick review, see the Topic 3.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3/selecting-an-experimental-design/study-guide/v0yhDrgjwaxeCkjNXNC1) and extra practice (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What's the difference between completely randomized design and randomized block design?

A completely randomized design (CRD) and a randomized block design (RBD) both use randomization, but they differ in how you control known sources of variation. In a CRD you randomly assign all experimental units to treatments with no grouping—good when units are fairly homogeneous. In an RBD you first form blocks of similar units based on a blocking variable (age, baseline score, location, etc.), then randomly assign treatments within each block. Blocking reduces within-group variability and helps control confounding from that known factor, so you get more precise comparisons of treatment effects. Use CRD when blocking isn’t practical or units are similar; use RBD when a strong, measurable source of variation exists and you want to remove its influence. For AP exam questions (CED VAR-3.D), be ready to justify the design choice by naming the blocking variable, explaining how it reduces variability/confounding, and noting randomization and replication. For a quick refresher, see the Topic 3.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3/selecting-an-experimental-design/study-guide/v0yhDrgjwaxeCkjNXNC1) and try practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

When should I use a matched pairs design vs a completely randomized design?

Use matched pairs when each experimental unit can be naturally paired so you can control for a big source of variability—either by (a) pairing two similar units (twins, matched patients) and randomly giving different treatments to each in the pair, or (b) using the same unit for both treatments (before/after or crossover). Matched pairs = a form of blocking: it reduces variability from the blocking variable and gives more power for the same sample size. Use a completely randomized design when units are independent and you can’t form meaningful pairs (or when blocking won’t reduce much variability). Trade-offs: matched pairs reduce confounding by the paired characteristic but can’t assess pair-by-treatment interaction and sometimes are harder to implement. Completely randomized designs are simpler, avoid carryover issues, and are fine when randomization balances other factors. Always randomize treatment assignment and replicate enough units. For AP review, see Topic 3.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3/selecting-an-experimental-design/study-guide/v0yhDrgjwaxeCkjNXNC1) and Unit 3 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3). For extra practice, try problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

I'm confused about experimental designs - how do I tell which one is best for a given situation?

Start by matching the research question and practical limits to the design. Quick checklist: - If units are exchangeable and you just compare treatments → completely randomized design (simple, needs good replication). - If a nuisance variable (age, school, baseline score) affects response → block on that variable (randomized block design) to reduce variability. - If each subject can get both treatments (time order OK) → matched pairs or crossover (paired comparisons give more power; watch for carryover in crossover). - If multiple blocking factors (rows × columns) → Latin square (controls two blocking sources). - Always randomize treatment assignment, include control/placebo when causal inference is needed, and blind if possible to reduce bias. Choose the design that minimizes confounding and maximizes precision given resources (sample size, time, ethics). Explain why your choice is appropriate on the exam (CED VAR-3.D): mention experimental unit, blocking variable, replication, and how randomization/ blinding reduce bias. For a focused review, see the Topic 3.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3/selecting-an-experimental-design/study-guide/v0yhDrgjwaxeCkjNXNC1) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What are the advantages and disadvantages of each type of experimental design?

Short version: each design trades control of variability, bias, and resources. - Completely randomized design (CRD): Advantages—simple, good when experimental units are homogeneous, randomization removes bias. Disadvantages—larger unexplained variation if units differ, less power. Good for AP when you want a baseline randomized controlled trial idea. - Randomized block design: Advantages—blocks reduce variability from a known blocking variable (age, school), increases power. Disadvantages—need enough units in each block; can’t block on too many factors. - Matched pairs: Advantages—pairs (or before/after) control for subject-level variability, strong for small samples. Disadvantages—matching can be hard; removes ability to estimate some effects separately. - Crossover design: Advantages—each subject gets multiple treatments (more power), controls between-subject variability. Disadvantages—carryover effects (need washout), not good if treatment has lasting effects. - Latin square: Advantages—controls two blocking factors (rows, columns) plus treatments; efficient. Disadvantages—complex, requires equal replication and no interactions with blocks. Other practical notes: always randomize and replicate; use placebo/control and blinding (single/double) to reduce confounding and bias. For exam, be ready to justify which design fits the question, mention blocking, randomization, replication, and possible confounding (CED VAR-3.D.1). For a quick study review see the Topic 3.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3/selecting-an-experimental-design/study-guide/v0yhDrgjwaxeCkjNXNC1) and Unit 3 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3). For extra practice, try the practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I explain why I chose a specific experimental design on the FRQ?

Say the design name, then justify it with 3 quick points: how it fits the question, how it controls variation/confounding, and practical constraints. Example structure you can use on the FRQ: 1. State the design (e.g., “I would use a randomized block design.”). 2. Identify units, factor(s), treatments, block variable, and control/placebo if used (CED keywords). 3. Give reasons: (a) randomization to avoid bias, (b) blocking to reduce variability from [blocking variable], (c) replication for precision, (d) blinding/placebo to reduce placebo/observer effects. Mention one downside if relevant (cost, carryover, or small sample size). Short concrete example: “Use a randomized block design. Experimental units = patients; factor = drug dose (low, high); block on age group because age affects response. Randomly assign treatments within each block and replicate 20 patients per treatment. Blocking reduces within-group variability and controls a likely confound; randomization prevents systematic bias; replication improves precision. A crossover could save subjects but risks carryover, so it’s inappropriate here.” That hits VAR-3.D (advantages/disadvantages of designs). For extra practice and FRQ wording tips see the Topic 3.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3/selecting-an-experimental-design/study-guide/v0yhDrgjwaxeCkjNXNC1) and try problems at (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

When do I use blocking in an experiment and when do I not?

Use blocking when there’s a known source of variability (a nuisance factor) that you can group units by so that differences from that factor won’t hide the treatment effect. Examples: age, classroom, baseline score, or machine batch. A randomized block design (or matched pairs if blocks of size 2) makes blocks homogeneous, then randomly assign treatments within each block—this reduces within-group variability and increases power (VAR-3.D, CED keywords: Randomized block design, Blocking variable, Experimental unit). Don’t block when you don’t have a clear nuisance variable, when blocks would be tiny (too few units), or when blocking would confound treatment with the block (e.g., each treatment only happens in one block). If blocking can’t be done, use a completely randomized design and rely on replication and randomization to control variation. For AP help on choosing designs and examples, check the Topic 3.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3/selecting-an-experimental-design/study-guide/v0yhDrgjwaxeCkjNXNC1) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What's the step by step process for deciding between different experimental designs?

Step-by-step quick guide to pick an experimental design (AP Vars: VAR-3.D): 1. State the research question and factors (treatments, levels). Be specific about the response and experimental units. 2. Ask about constraints: how many units, time, cost, and ethical limits. These affect feasibility and replication. 3. Identify major sources of variability or confounding (covariates you can block on). If a clear blocking variable exists, consider a randomized block design. 4. Match design to question: - Single factor, independent units → completely randomized design. - Known nuisance variable (sex, age, location) → randomized block design. - Pairs of similar units or before/after on same subject → matched pairs or crossover. - Many factors with interactions → factorial design (watch for interaction effects). - Repeated treatments on same subject with washout → crossover. - Multiple nuisance sources that form rows/columns → Latin square. 5. Ensure randomization and replication to reduce bias and estimate variability; use blinding (single/double) and placebo when possible. 6. Check for confounding, feasibility, and ethical concerns; pick the simplest design that answers the question with enough power. 7. Write the plan, simulate/sample-size check, and revise. For more AP-aligned detail see the Topic 3.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3/selecting-an-experimental-design/study-guide/v0yhDrgjwaxeCkjNXNC1). Want more practice? Fiveable has tons of practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics) and a Unit 3 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3).

I don't understand when to use completely randomized vs randomized block vs matched pairs - can someone explain?

Use a completely randomized design when your experimental units are essentially the same or you don’t have a clear source of extra variability to control. Randomly assign all units to treatments—simple, good for avoiding bias, but can leave important variation (like age or baseline score) unexplained. Use a randomized block design when you can identify a blocking variable that affects the response (e.g., gender, baseline score, classroom). First group similar units into blocks, then randomly assign treatments within each block. Blocking reduces unwanted variability and helps avoid confounding between block and treatment (CED keywords: blocking variable, experimental unit, treatment). Matched pairs is a special randomized block design with block size 2: either (a) two similar units paired and given different treatments, or (b) the same unit gets both treatments in random order (crossover). Matched pairs is best when you can pair closely on a key confounder or use the same subject twice—it maximizes power with small samples. On the AP exam you’ll need to explain why your choice reduces variability/confounding and mention replication/randomization (VAR-3.D). For a quick review see the Topic 3.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3/selecting-an-experimental-design/study-guide/v0yhDrgjwaxeCkjNXNC1), the Unit 3 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3), and tons of practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I identify what type of experimental design a problem is asking for?

Look for how units are assigned and what’s being controlled. Key clues: - Completely randomized design: experimental units are randomly assigned to all treatments (no blocks). If prompt just says “randomly assign n subjects to treatments,” pick this. - Randomized block design: units are grouped by a blocking variable (age, gender) then randomized within blocks. Look for “blocked by” or comparable groups. - Matched pairs / repeated measures: pairs of similar subjects or the same subject gets two treatments (before/after). If each person gets both treatments or is paired, it’s matched pairs or crossover. - Crossover: subjects receive treatments in different periods with washout; look for “periods” or order effects. - Latin square: blocking on two nuisance variables (rows/columns) plus treatments—rare but noted. Also check for control group, placebo, blinding, replication, and whether factors or interactions are involved. Explain why the choice matters (confounding, controlling variability) as the CED requires (VAR-3.D). For a quick review, see the Topic 3.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3/selecting-an-experimental-design/v0yhDrgjwaxeCkjNXNC1), the Unit 3 overview (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3), and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What factors should I consider when selecting an experimental design?

When choosing an experimental design, think like an AP grader: match the design to the question, the units, and your resources. Checklist: - Question & factor(s): how many factors and levels? (influences whether you use completely randomized, randomized block, matched pairs, crossover, Latin square) - Experimental units & treatments: are units independent? (if paired measurements, use matched pairs or crossover) - Blocking & confounding: block on known sources of variability to reduce noise and avoid confounding factors and interaction effects - Randomization & replication: random assignment reduces bias; replicate enough units to estimate variability and meet exam conditions - Controls, placebos, blinding: include control group/placebo and use single- or double-blind to reduce bias - Practical limits: cost, time, ethics—may force simpler designs or fewer levels If you want a quick AP-aligned rundown and examples, check the Topic 3.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3/selecting-an-experimental-design/study-guide/v0yhDrgjwaxeCkjNXNC1). For broader Unit 3 review, see (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3) and practice Qs (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

Why would I choose a matched pairs design over a completely randomized design?

Choose matched pairs when you can pair experimental units so each pair is similar on strong sources of variation (same person before/after, twins, or two very similar subjects). Matched pairs is just a randomized block design with block size 2: it blocks by the pairing variable so between-pair variation is removed. That usually lowers the standard error, increases statistical power, and makes it easier to detect treatment effects than a completely randomized design with the same sample size. Use matched pairs when subject-level differences would otherwise confound results; use a completely randomized design when pairing isn’t possible or when carryover/interaction effects (e.g., in crossover designs) would bias results. Remember to still randomize treatment assignment within pairs and replicate enough pairs for inference (CED VAR-3.D: weigh advantages/disadvantages). For a quick refresher on picking designs, see the Topic 3.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3/selecting-an-experimental-design/study-guide/v0yhDrgjwaxeCkjNXNC1) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

I missed class on experimental designs - what's the difference between all the types?

Here’s a quick, exam-focused rundown so you can tell the designs apart and why you’d pick each one (VAR-3.D): - Completely randomized design: randomly assign experimental units to treatments. Best when units are similar; simplest; randomization reduces bias. - Randomized block design: group units by a blocking variable (like age) then randomize within blocks. Cuts variability from known sources; prevents confounding. - Matched pairs: a special block of size 2—either two similar subjects paired or the same subject gets both treatments (one at a time). Good for reducing variability. - Crossover design: each subject gets multiple treatments in sequence (with washout). Paired comparisons and checks for carryover effects. - Latin square: blocks in two directions (e.g., rows and columns) to control two nuisance factors when sample size is limited. - Randomized controlled trial (RCT), control group, placebo, single/double-blind, replication: standard safeguards to reduce bias, placebo effects, and increase power. Key AP stuff: name the design, justify blocking/randomization/replication, and note possible confounding or interaction effects. For a deeper guide and examples, see the Topic 3.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3/selecting-an-experimental-design/study-guide/v0yhDrgjwaxeCkjNXNC1) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

How do I justify my choice of experimental design in a free response question?

Start by naming the design you chose (e.g., completely randomized, randomized block, matched pairs, crossover) and cite the CED learning objective VAR-3.D: you must explain why that design is appropriate. Then justify with 3 short points: 1) Purpose & units—state the question of interest and the experimental units (who/what gets treatments). 2) Key features—say how your design handles variation: randomization to remove bias, blocking or matched pairs to control known sources of variability, replication for precision, and blinding/placebo to reduce bias. Use CED terms (blocking variable, treatment, control group, double-blind). 3) Tradeoffs—note one advantage and one disadvantage given resources or logistics (e.g., blocking reduces variability but needs a larger sample; crossover controls subject differences but risks carryover). Quick FRQ template: “I choose a [design]. The experimental units are [units]. Randomization ensures unbiased treatment assignment. Because [blocking variable] strongly affects the response, I use blocking/matched pairs to reduce variability and increase power. Replication of [n per treatment] improves precision. A potential drawback is [cost/carryover], but overall this design best balances control of confounding and available resources.” For more examples and wording to use on the exam, see the Topic 3.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3/selecting-an-experimental-design/study-guide/v0yhDrgjwaxeCkjNXNC1). For broader review and extra practice, check Unit 3 (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3) and the 1000+ practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).

What are the key things to look for in a word problem to determine the best experimental design?

Look for clues in the wording that map to the common designs and AP keywords. Quick checklist: - What's the question? If you want cause→effect, you need an experiment (randomized controlled trial, treatments, control/placebo). - Are units paired or naturally matched (twins, before/after)? → matched pairs or crossover. - Is there an obvious blocking variable (age, gender, site)? → randomized block design (blocks then randomize treatments). - Are all experimental units randomly assigned to all treatments with no blocking? → completely randomized design. - Do units get multiple treatments in different orders? → crossover design (watch for carryover). - Do you need to control two blocking factors (rows/columns)? → Latin square. - Look for words: “randomly assigned,” “paired,” “block,” “placebo,” “double-blind,” “replicate”—these tell you design and whether blinding/replication are possible. - Note constraints: small sample, ethical limits, or possible confounding—these affect which design is feasible. For more examples and how the AP tests this (VAR-3.D), see the Topic 3.6 study guide (https://library.fiveable.me/ap-statistics/unit-3/selecting-an-experimental-design/study-guide/v0yhDrgjwaxeCkjNXNC1) and practice problems (https://library.fiveable.me/practice/ap-statistics).